This is the second of two parts. You can find Part 1 here.

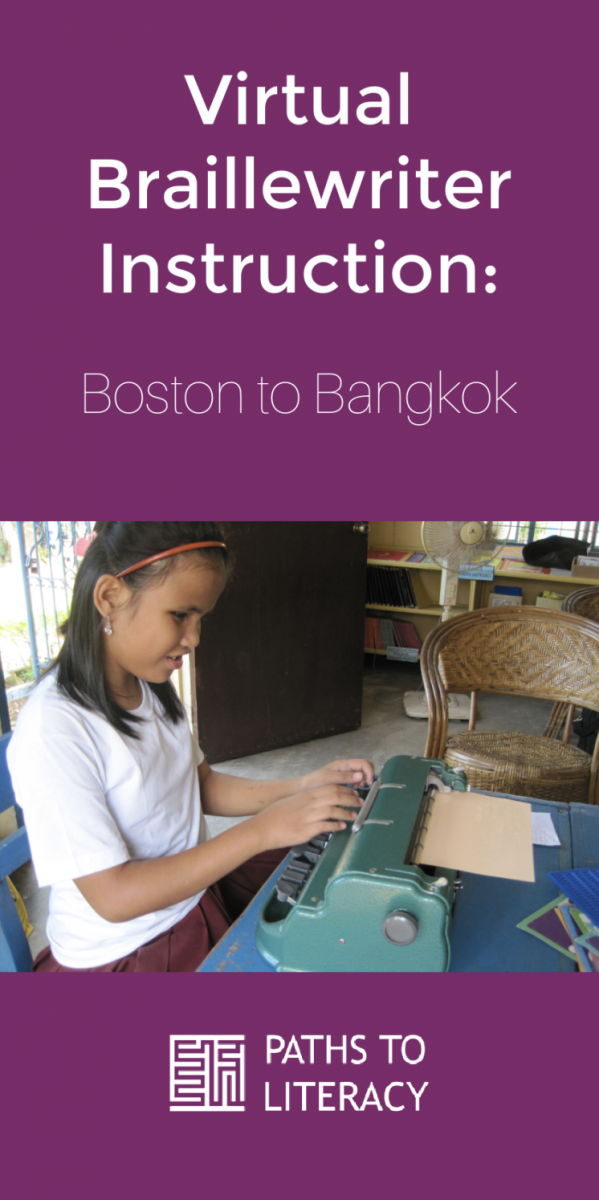

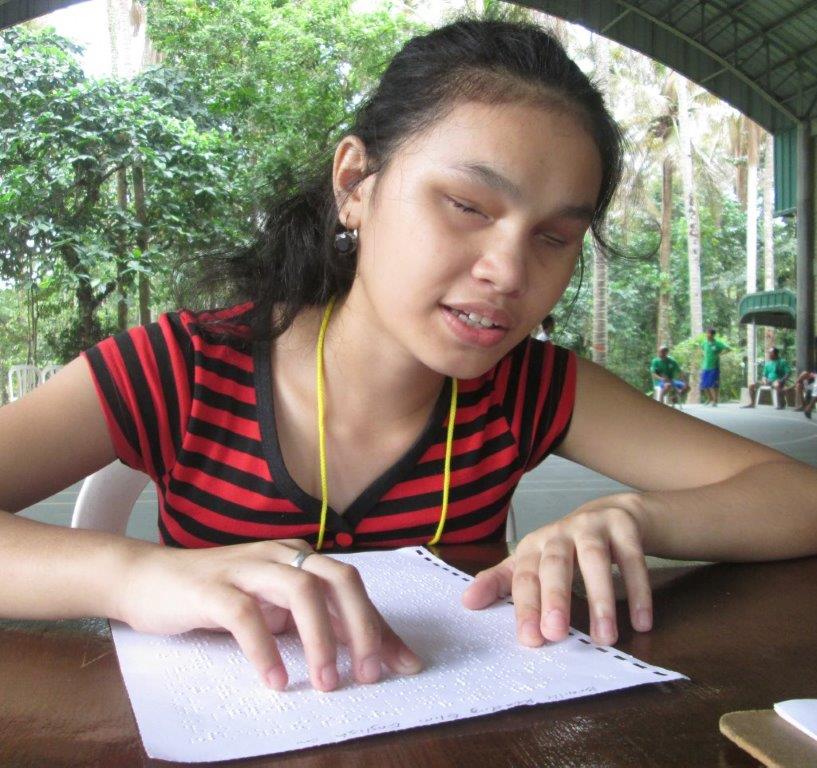

We at Perkins International (PI) are virtually consulting and providing training for two teams of teachers at the Bangkok School for the Blind (BSB) in Thailand. One team works with 5th grade students in an academic setting; the other works with younger students with MDVI (multiple disabilities including visual impairment/blindness). As in many programs in Asia, students at BSB typically used the slate and stylus to write braille. Teaching braillewriter skills fit within the broader context of our training goals at BSB. The students with MDVI were having difficulty learning to write braille with the slate and stylus, but were already showing interest and potential in learning to write with braillewriters. For the fifth grade students, the mechanics of using only slate and stylus to write was limiting their ability to demonstrate higher level thinking skills in their writing.

The school already had a number of Perkins braillewriters available in their classrooms. One of our goals was that both the teachers already skilled in using the braillewriter and those relatively new to it had shared knowledge of braillewriters; teaching from year to year would be clearer to the students when all the teachers used the same braillewriter labels and procedures. Beyond this, the teachers asked for more ideas in teaching braillewriter skills to their students and to their students’ families.

Previous Braillewriter Instruction in Asia

Face-to-face braillewriter instruction in other countries and cultures was not a new assignment for Perkins International staff. Through three- to five-day workshops in China with interpreters and Chinese co-teachers, Laurie had successfully taught teachers the mechanics and advantages/limitations of braillewriters. We had developed lesson plans in writing and editing the Chinese alphabet, numbers and passages with braillewriters. We had discussed how braillewriters could be combined with the slate and stylus and computer-generated braille as an important literacy tool. We had designed and implemented student competitions so that teachers in the workshop could practice introducing braillewriter teaching skills at the same time as they were learning the skills themselves.

Challenges of Virtual Braillewriter Instruction at BSB

But how could we virtually share our recommended braillewriter labels, mechanics and procedures with BSB teachers, from Boston to Bangkok? How could we present this virtually in a Thai-speaking country….in a time zone that was twelve hours different from our own…where we could teach only through interpreters and when we could watch the teachers on Zoom only as their cameras defined our viewpoints? And how could we use the same Zoom meeting to develop shared understanding among a team of school administrators and teachers who are leading the transformation of their school? How could we present this in a format that these teachers could later replicate in introducing braillewriters to colleagues and families of their students? And how could we do so in a way that recognized some of their colleagues were unfamiliar with using a braillewriter, while other colleagues were familiar with using a braillewriter themselves, but reluctant to allow their students to use braillewriters?

Thanks to Bangkok School for the Blind

We were enthusiastic about addressing these challenges, and grateful to the Board, the administrators, and the teachers at the Bangkok School for the Blind for their commitment in working alongside us in this new virtual model. BSB gave us support and advice from both their Board and their administrators, they gave us their time (including coverage for teachers who met with us during instructional hours), and they gave us four dedicated Thai-English speakers as interpreters. We especially appreciate the support of Ms. Oratai Thanajaro, BSB Board member and Foundation member, who serves as a valuable liaison for our BSB and Perkins International teams.

Virtual Braillewriter Exercise in English

Our first step in this project was to plan how to introduce basic braillewriter skills virtually in English. We created our own diagram of braillewriter parts labeled in English, and we developed an 18-step exercise in loading and unloading paper in a braillewriter, and writing and editing braille while the paper was still loaded. (We posted this on Paths to Literacy: A Virtual Introduction to Braillewriters.)

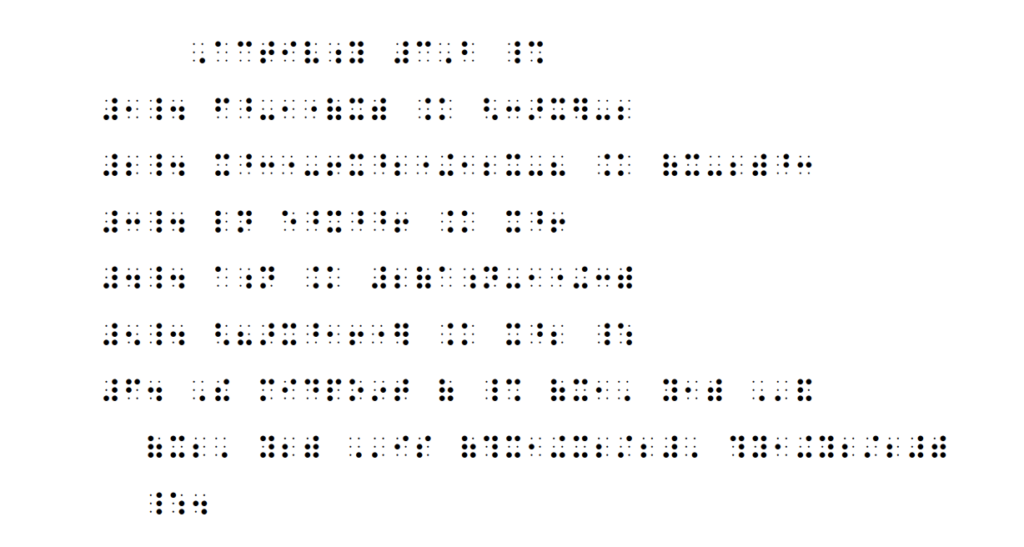

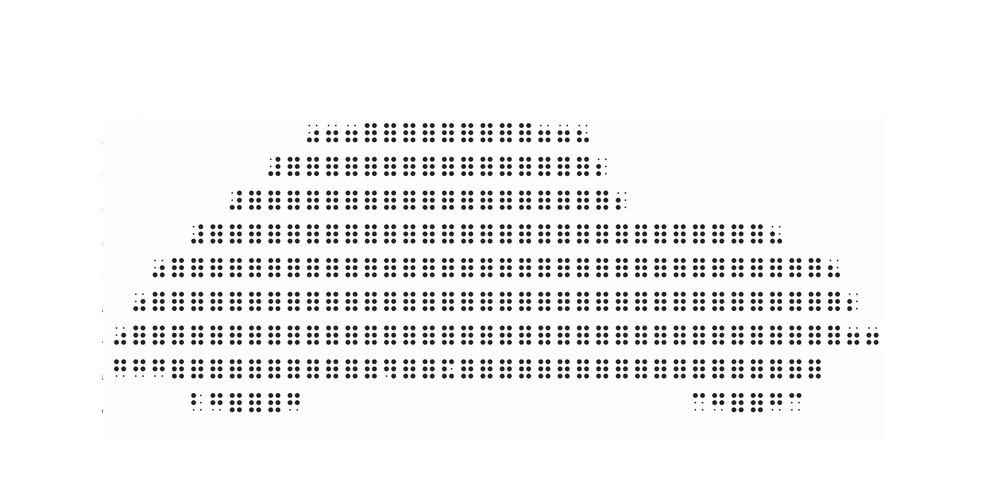

Next, it was time to plan application of this exercise at our partner school in Bangkok. In preparation, we emailed a list of our English brailler labels to our partner team and asked them to translate them into Thai. We added these Thai labels to the English labels on our Perkins Braillewriter diagram. We gave this photograph to each of our Bangkok teachers and asked them to bring it to another teacher or family member who was already skilled in using a braillewriter and ask them to demonstrate these parts and functions. We similarly asked our interpreters to translate our 18-step exercise (below); we appreciated their taking great care here, asking for clarification about a number of steps in order to translate it most accurately.

The Virtual Lesson Set-Up

With the assurance that in Boston and Bangkok we had common understanding of braillewriter names and functions, our three Perkins International team members (Laurie, Debbie, and Ami Tango-Limketkai) met on Zoom with: five BSB teachers, several Thai school administrators and Board members, and 2 interpreters. (Orasa Kanjanachoosak did most of the live interpreting during our session. Siriporn (Noie) Tantaopas stepped in to interpret technical content related to visual impairment and blindness. Samart Ratanasakorn translated all the printed material into Thai weeks before the meeting; and Pisit Prougestaporn provided additional support with translation of documents. Both Samart and Noie are graduates of Perkins Educational Leadership Program, and thus quite familiar with the technical content.)

The five Thai teachers sat together at one table, each with their own braillewriter and paper, with one camera focused on them. Including our PI team, the Zoom session included about 12-14 people on 8-9 devices, in at least 8 different locations. With our 12-hour time difference, our meeting was scheduled in the evening for Boston, which was early the next morning for Bangkok.

Introduction to the Virtual Lesson

To start the lesson, we reviewed the two purposes of the 18-step exercise: to ensure shared understanding and to provide resources for the teachers to train others in using braillewriters. We asked for a volunteer to read the exercise in Thai after we said each number (see exercise below.) In yet another indication of the commitment of the school community, Mr. Prasong (Director of School Management) volunteered. We asked the teachers to follow him, step-by-step, while we at Perkins were available to call out next numbers, and to comment and clarify as needed. If teachers finished before their colleagues, we asked them to help their colleagues or simply to wait so everyone was working together. The interpreters were poised to translate our English into Thai for our Bangkok team members, and their comments/questions from Thai to English for us.

1. The Virtual Lesson

At our prompt (“number 1,”) Mr. Prasong started by reading step one in Thai, จัดตำแหน่งการนั่งให้เหมาะสม โดยให้แป้นพิมพ์อยู่ต่ำกว่าข้อศอกของคุณ (in English, “Find a position so the keys are lower than your elbows.”) We had observed in past consultations that this positioning, which maximizes core strength in braille writing, was not universal practice at the school, so we began by reviewing why it was important and examples of how to achieve it, such as standing while the braillewriter was on the table, or adjusting the height of the chair/ table. The teachers then followed the Director’s instructions as everyone else observed as much as the camera in the teachers’ room allowed. Then we said “number 2,” he read the second step in Thai, the teachers followed it, and so on through loading the paper, writing and editing, and unloading the paper. The exercise proceeded, although with some unnecessary pauses when, in hindsight, the teachers had finished steps but this wasn’t apparent to us in viewing the camera in their room. (In retrospect, we realize that to pace the exercise, it may have been preferable for the Director or another volunteer Thai reader to call out each of the steps of the exercise, rather than waiting for us to do this.)

Reflection on Goals

Did we achieve our goals for our first international virtual braillewriter lesson? Looking at each of them, one at a time:

2. How could we virtually present our recommended braillewriter labels, mechanics and procedures to teachers in other countries who spoke a different language? As Laurie wrote in Part I of this series, “basically, we need to do it all with words.” In this example, the translators took great care to establish accuracy in our written words, and to be consistent with them in oral interpreting. This included their using one interpreter for most of the Zoom session, but another, who was a teacher of students with MDVI, for the technical content specific to visual impairment/blindness.

3. How could we most effectively teach when everything needed to go through interpreters? This was of high value to us since, as we say, “we’re only as good as our interpreters.” BSB generously provided three interpreters. We had already worked with them for several months so we had relationships with them. Prior to our Zoom session we carefully reviewed specific braillewriter terminology with them, and we were also comfortable with pacing and with stopping to discuss clarification of unfamiliar words or phrases both in advance and during sessions. We chose clear terms and idiom-free phrasing as much as possible.

4. How could we meet with teachers in a time zone that was twelve hours different from our own? Beginning in early morning at the start of their school day, our Thai partners worked around instructional time, and we in the U.S. worked around our evening routines. On our calendars, we needed to remember that this meant we met on different days (for example, Tuesday evening Boston/ Wednesday morning Bangkok).

5. How could we observe fully on Zoom, where the camera in the teachers’ room defined and limited our viewpoints? The camera’s visual range has been a continuing challenge for our virtual instruction, since we were seldom aware of what was happening in a room beyond our Zoom screen. When things seemed confusing, our Thai colleagues sometimes offered an explanation, for example that something we referred to wasn’t available. However, without being able to scan full rooms, we realized we might have been missing information that was key to us, but was outside the camera’s field of view. In retrospect, it may have been helpful to request that someone use a second device to periodically scan the full room where the teachers were completing the exercise, and/or periodically zoom in for closer views of individual teachers as they used their braillewriters.

6. How could we use the same Zoom meeting to develop shared understanding of the ease and unique benefits of the braillewriter among a team of school administrators and teachers who are leading the transformation of their school? The active participation of BSB leaders and Board members reflects their interest and their commitment to the continued growth of their program. Including this broad team has numerous benefits. With their decision-making authority, administrators can approve recommendations on the spot, support teachers in implementing new strategies, and provide informed follow-through. In fact, it turned out to be a boost that Mr. Prasong reinforced several of our suggested strategies as he read the exercise in Thai during our session.

7. How could we present this material in a format that the teachers could later replicate in introducing braillewriters to colleagues and families of the students? Preparing instructional materials in a bilingual Thai/English format and modeling the lesson with the teachers provided our Bangkok colleagues with both written instructional materials they can use, and a model lesson plan they can follow to introduce braillewriters to colleagues and families of students.

Moving Ahead

As we adjust to our ever-changing global conditions, we need to continue to be nimble and creative in supporting children with visual impairment/blindness/multiple disabilities and their educators and families. Like educators the world over, we are prepared to move flexibly back and forth between in person and virtual formats. Many of the strategies and lessons learned during this virtual braillewriter lesson are applicable to other virtual international consultations, such as the importance of having a relationship with interpreters, investing time in reviewing terminology with interpreters ahead of time, and having a shared understanding of terminology. In addition, for virtual trainings it is very helpful to have a partner/colleague on the ground who can reinforce application of skills and monitor for understanding, and to include a team of administrators together with teachers in some trainings can support follow through and implementation of new strategies.

We at Perkins International are grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with our committed colleagues at Bangkok School for the Blind, and all our dedicated colleagues and partners around the world. Together we are working to reach our vision of a world in which every child learns and thrives as a valued member of a family, school and community.

Braillewriter Practice

แบบฝึกการใช้เครื่องพิมพ์ดีดอักษรเบรลล์

Laurel J. Hudson, PhD

Putting Paper in Braillewriter:

การใส่กระดาษในเครื่องพิมพ์อักษรเบรลล์:

Writing, and Taking Paper out of Braillewriter:

การพิมพ์ และนำกระดาษออกจากเครื่องพิมพ์ดีดอักษรเบรลล์

Download Braillewriter Practice แบบฝึกการใช้เครื่องพิมพ์ดีดอักษรเบรลล์.