Learning to read actually begins at birth, as there is so much that goes into the whole process. It includes developing basic cognitive concepts, motor skills, language & communication, and more. For children who are learning to read braille, all of these skills are necessary too, but it is also essential for them to develop their fine motor skills and tactile discrimination.

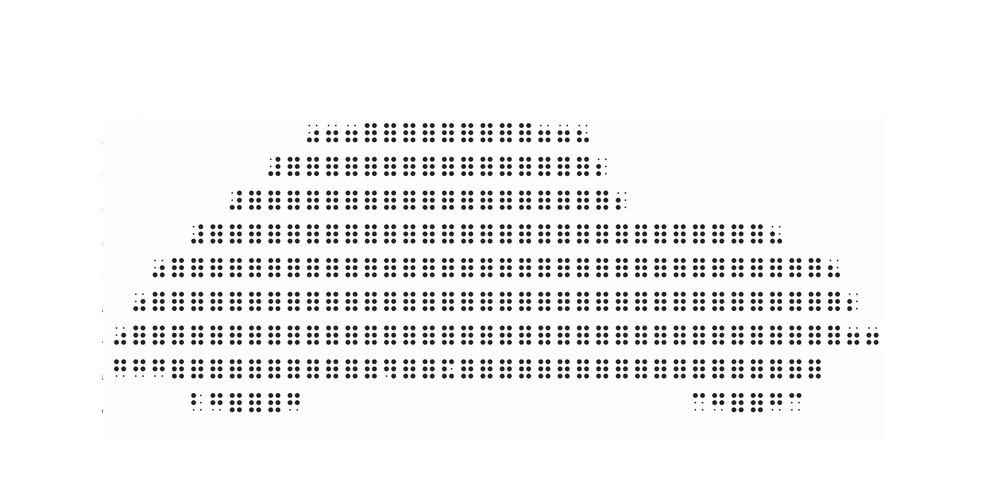

1. Be sure that the child has LOTS of access to braille EVERYWHERE!

Remember that children who are sighted have seen MILLIONS and MILLIONS of words before they begin to read. There is typically print everywhere: on boxes and containers of food, shampoo, toothpaste that can be seen at home, in shops, and on the television. Usually there are many examples of print in a house, including newspapers, magazines, books, correspondence, computer, lists. Now think about how much practice and exposure a child who is sighted has had before formal reading instruction begins. It is crucial to provide as much exposure to braille in the environment as you can. Items in the house should be labeled in braille, and every child should have loads of beginning reading materials in braille available that they can find.

2. Give the child lots of practice developing fine motor or handskills.

Encourage children to open and close all different types of containers, and to do all types of fasteners on clothing (buttons, snaps. zippers, etc.) Invite them to help with cooking chores — stirring, scooping, chopping, pouring. While these may not seem important to learning to read, they are!

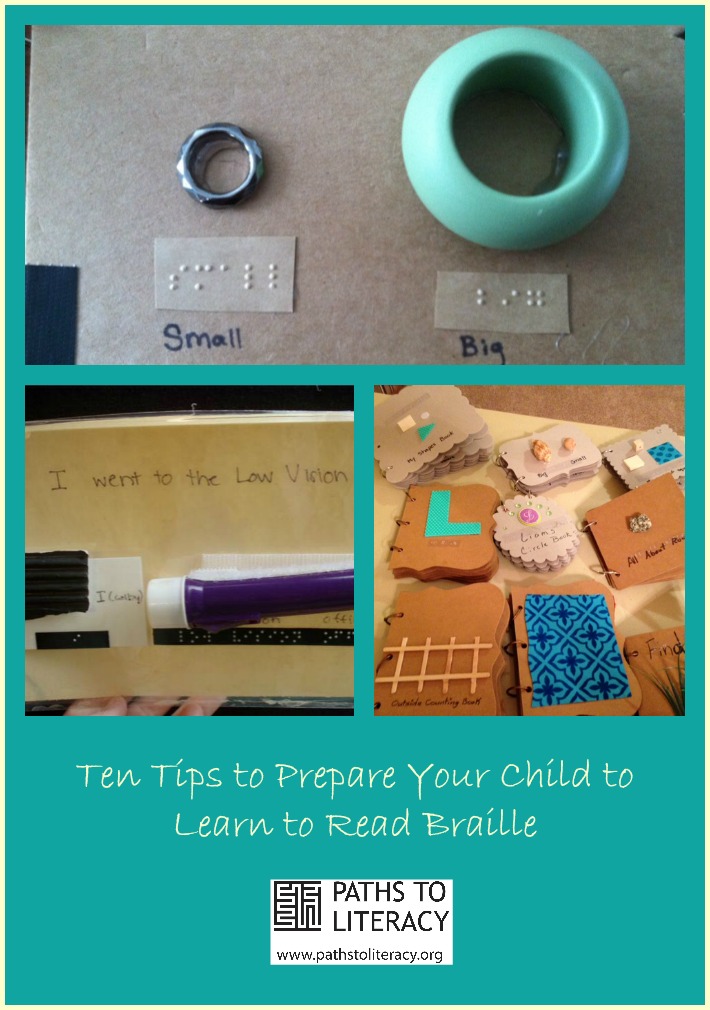

3. Have the child sort, match, and categorize items.

Ask the child to sort different types of materials — buttons, beans, nuts, coins. It can be anything, but it is important that he or she be able to distinguish different properties of items. Have him sort big/little, rough/smooth, squares/triangles, etc. Be sure to set up the sorting task with distinct places to put items and an organized workspace. For example, mixed coins can be placed on a large plate and quarters can go into one bowl on the left and pennies can go into a bowl on the right. The child doesn’t need to understand the value of the coins at this point, but just to recognize the difference in size and tactile distinctions. Have the child follow patterns, such as big, little, big, little, etc.

4. Give the child practice telling stories and sequencing events.

Decoding braille is only part of the process of learning to read. Language development is an essential part of being ready to read. Ask the child to tell you what he or she did today. Have him name 5 things he bought at the market. Ask her what happened yesterday. What was the first thing he did when he got up? What happened after that? What did she do before bed?

5. Familiarize the Child with Positional Concepts, Directionality and Spatial Orientation.

Give the child practice with positional concepts, such as up/down; above/below; in front/in back of/next to; top/middle/bottom; left/middle/right. Ask her to show these things on herself (e.g. “Put the cup behind you.”) Then ask her to do it with two objects (“Put the book above the plate.”) Ask him to point to these locations on a page. (“Show me the bottom left part of the page.”)

6. Practice counting.

-

Count things in the natural context throughout the day. Count the number of shirts in the laundry basket, the number of forks in the sink, the steps from one location to the next.

-

Count how many people are going to site at the table for dinner. Then count the chairs and silverware. Match one plate to each place and one cup to each plate. (1:1 correspondence)

-

Ask the child how many items are in a set. For example give him 8 spoons and ask “How many spoons are there?” Next give him a larger array of items and ask him to make a smaller set. For example, give him 10 nuts and ask him to give you 6.

7. Provide Opportunities to Increase Tactile Discrimination.

Create tactile books to give the child exposure to different items. See these posts for some ideas on object books and tactile books:

Next, give the child more formal practice by brailling single cells that are the same, with one letter that is different. For example, you might braille a line of a, a, a, a, a, l, a, a, a. Ask the child to find the one that’s different. Braille his name and put a different word in and ask him to find it. For example, Ahmed, Ahmed, Ahmed, Ahmed, puppy, Ahmed, Ahmed, Ahmed. You can make this harder and harder as he gets better at it.

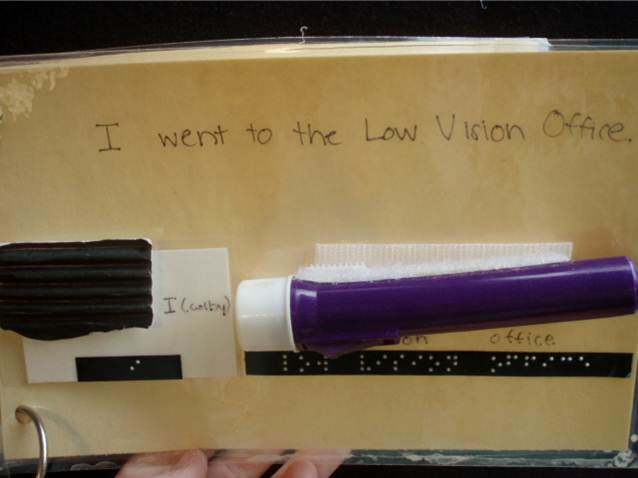

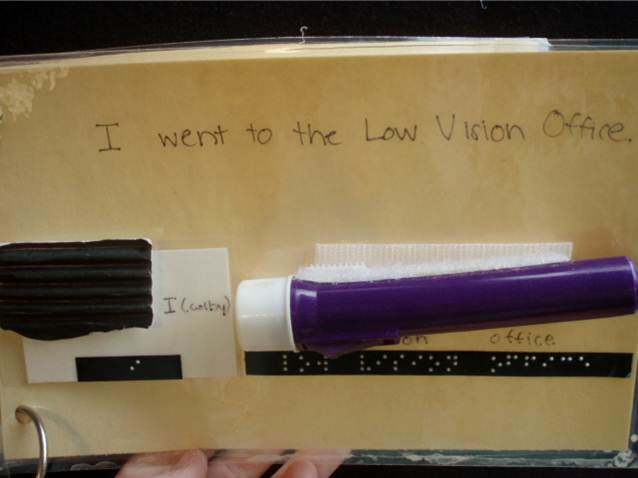

8. Create Experience Stories.

Invite the child to dictate a story about an event. Write down what she says in print and braille and then have her read it aloud with you over and over. This will help her to begin to understand that the braille code is associated with meaning, and thateach braille word on a page corresponds to a spoken word. This is also a motivating way to get started by creating her own books.

For more information about Experience Stories, see:

9. Encourage the Child to “Scribble” on the Braillewriter.

Reading and writing go hand in hand when developing literacy skills. Children who are sighted practice scribbling with crayons and markers long before they beging to learn to write actual letters. Similarly, children who are learning braille should have practice making marks on paper using a braillewriter or slate and stylus.

Read more about this: Scribbling with My Son Who Is Deafblind

10. Read every day!

As in the first point above, be sure that the child has lots of exposure to braille all around the house and in every environment possible. In addition, it is important to read stories with him or her every day. In the United States there are many ways to get free braille books. If you have difficulty getting access to books in braille, you can contact the Association for the Blind nearest to you. The exposure to braille in general is important, but it’s equally important for the child to begin to understand that braille is a code for spoken language.

Create tactile books to give the child exposure to different items. See these posts for some ideas on object books and tactile books:

Create tactile books to give the child exposure to different items. See these posts for some ideas on object books and tactile books: