Braille for Latecomers: Top Access Tips for Dual Media Learners

These tips are for those who are introduced to braille, after already having an ability to read print.

The point at which you decide to introduce braille will depend on many complex factors, and each child will be individual and unique. It is a delicate balance during this period of time, requires constant review, sensitive handling and management of the Team supporting the child and family to ensure support is appropriate and timely. Here are some considerations:

- Onset of eye condition—degenerative/sudden

- The emotional state of the child and family and the stage they are at in coming to terms with the sight loss

- The educational stage the child/young person is at, e.g. If the young person has reached GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) and has experienced unexpected sudden sight loss, the priorities for the year need to be established as early as possible, (e.g. What is the main focus, being able to take GCSE’s supported by a reader and scribe, or learning braille?)

- The young person’s memory skills

- The young person’s level of intelligence

- Level of finger sensitivity and fine motor skills

For example:

You may have a young person with low reasoning skills. but an excellent memory and good sensitivity of touch.

Or, the young person may have a high IQ, sensitivity of touch, an excellent memory, but may not be emotionally ready to learn braille. In these situations braille development is likely to be slow.

For many learning braille is an acceptance that they are blind, there is likely to be a grieving process that accompanies this period of time. It will be different for each child or young person and their feelings towards learning braille may change as the realisation about their vision becomes more apparent to them. Therefore during the transition period when print is becoming to difficult to access they will often want to keep reading print until it becomes inaccessible.

This needs careful handling, allowing them to read print may mean they will come to their own realisation, perhaps better than being told ‘you can’t read print any longer.’ Whilst vision is present, there maybe a need to look, making the acquisition of braille skills more tricky. It is really important to manage this stage delicately. You can only go at the pace of the child or young person, for some, this stage may last quite a while, the more we attempt to implement braille when they are not ready, the more resistant to braille they may become.

It is a fine line to tread, requires constant review and essential is the importance of ascertaining the child or young person’s feelings and views, in a constructive and structured way, e.g. avoid asking questions to which they can give you the answer they think you want to hear. E.g. “I’m fine.” In my time as a Head of Service for VI I supported three young people, different ages, all with different reasons for their sight loss, both sudden and unexpected sight loss and also as a result of a deteriorating condition. For each the impact was different, but not to be underestimated and in each case I led my team carefully through the stages of supporting the child and family. I found at this time that there is an overwhelming desire by all the professionals to support to the extent of “over supporting.” We can be in a huge hurry to introduce braille, because we are concerned about the child’s access, we want to re-skill them as soon as possible, to mend, to fix, to solve the problems. Whilst the child’s academic progress is very important, there are short term solutions to enabling access whilst space and time is given to enable an understanding of what has happened to take place, by both child and family.

Key points I learnt in supporting children with sudden sight loss

- There is no book which tells you exactly what to do in this situation, because circumstances, emotions and reactions for each is very individual.

- Take your time making decisions, make them in conjunction with your team, carefully, over a period of time.

- Allow time and space for the child and family to come to terms with what has happened, providing links to other organisations and to supportive information

- Definitely don’t feel you have to make hurried decisions about introducing braille to quickly instead find short term solutions to enable access, whilst this is thought about, allowing time to introduce the idea to the child and family and for the information to be absorbed and accepted. For some, the word “braille” has a significant impact on how they are feeling, timing and careful wording are crucial when this subject is introduced.

- Have one person to co-ordinate the team supporting the child, with clear communication channels about whom is liaising directly with the family, about what and how it is to be said.

- This information can then be shared carefully with the key team, to keep everyone abreast of developments.

General Tips

- Braille needs to be introduced with tact and sensitivity

- If you are met with resistance it may be better to leave until a later date when the young person is more accepting of their situationImportant to listen to the young person and respond to their need and work at their pace if this is the case.

- If resistance is met consider offering other access options for them to choose from, (keeping some control in the hands of the young person—they need to feel they are in the ‘driving seat’)

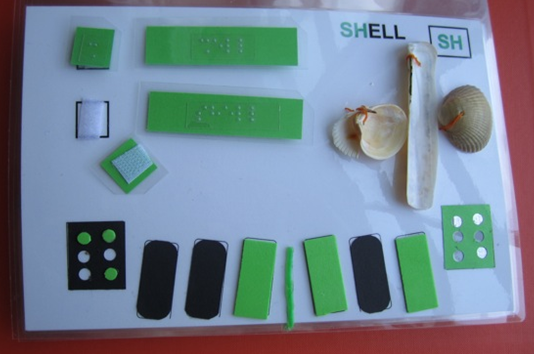

- Pre-Braille includes tactile sensitivity skill development and tracking skills practice. Just as for younger children learning to read braille for the first time, latecomers to Braille need to develop tactile sensitivity skills.

- It is important to return to these skills and teach alongside the introduction of braille once this stage of development is reached. This will help refine their skills and build up speed.

- Use the activities set out in Fantastic Fingers or ensure that you include a systematic approach from being able to feel large hand sized 3D objects down to smaller 3D objects—to 2D shapes getting smaller and smaller until the child is feeling them under their fingerpad. Ideally daily sessions enable progress to be maintained. When I was teaching braille to Latecomers I included a daily session (approx 20-30 mins) with them.

- Depending on the child’s age fine motor skills need to be reinforced. It takes a considerable amount of strength to press the keys on the Perkins Braille Writer and these may need work on to develop.

- It is important to make these activities fun and to use a variety of games to make the braille lesson more interesting and motivating.

Considerations whilst Teaching Braille to Latecomers

- At the beginning, meaning has to take second place to mechanical recognition of signs and the building of these into words.

- Some young people coming to braille as a latecomer may never have really mastered print reading. For them some phonic training will be needed and as the signs are taught practice in sound and blend recognition will be useful.

- The desire to look at the dots can be a problem for young people who are on the borderline of print access. This is tricky becausse they may still be able to use their vision to a certain degree. There are different views – those that feel it is important to equip the child with braille skills in preparation for when their sight deteriorates and they can no longer access print and those that that think it better to wait until this time. In my experience, it is different for each child, there is no right or wrong way, or again book which will direct you. I was guided by the child and how they were coming to terms with their visual loss, the educational stage they were at, what they preferred and more besides… again a delicate balance taking time and much thought to reach.

- There is also an emotional aspect for the child in that they are being constantly reminded that soon they will not be able to see, they may see learning braille as a positive, motivating them on, or they may feel resentful about having to learn braille – it will be individual to the child or young person.

Acquisition of Braille Skills:

- The child may take time to recognise and synthesise some signs and combinations of the code.

- Any sign which has more than four dots, especially when positioned beside another, also with more than four dots, may take time to learn

- Letters with one dot difference, plus letters with only one dot at the top or bottom of the cell and no middle dots, some may miss discriminating the bottom dots completely.

- Signs which are reversals of others (usually taught well apart)

- Real blanks and silences can occur in reading braille. It is difficult to distinguish between these and the ’working silence’ which accompanies the normal recognition and synthesising of signs.

- Keep a constant check that the correct cell is being felt and the finger pads are not reading across a couple of cells, e.g. talk about top, middle and bottom rather than dot numbers (to discourage reading across two lines of braille.

- Where words as a whole take time to distinguish or understand, “informed guessing” can be useful once two or three letters are recognised.

- Activities to encourage a good reading speed is a main aim from the beginning.

- Build in activities based on timing, in which the child scans for specific signs or contractions at various speeds. These can be helpful (at a later stage) in eliminating scrubbing and too heavy a pressure of the hands.

- Steady, daily practice, games to build in scanning exercises (where fingers slide along a line of braille picking out a particular sign) or lists of words skimmed along to find a specific one.

- Many children tend to check a word a number of times to make sure it is correct. Offer reassurance, and on occasion request they miss out words not deciphered first time, to demonstrate that they can still make sense of the passage

Braille Reading Programme for Latecomers

Braille in Easy Steps is a contracted braille course from RNIB made up of 16 books, designed for latecomers (pupils between the ages of about 10 to 14) who are literate in print but are transferring to braille.

- Book 1 consists of pre-braille skills. No previous knowledge of braille is assumed, and the emphasis is on reading. The complete contracted braille code is introduced in small steps, with practice reading material in the form of quizzes, activities and stories.

- Some of the longer stories are accompanied by tactile maps and plans to add interest, and develop search and scan techniques. The capital letter sign is used throughout.

- The advantages of this scheme are that it goes from the beginning right through the code. It takes note of the need for practice at each stage and introduces signs which could be mistaken for one another well spaced out.

- In many of the shorter bits and pieces a response is required from the reader so the teacher is able to assess how much information is being assimilated.