CVI and the Evaluation of Functional Vision

Overview of CVI (Cortical Visual Impairment) with diagnosis, characteristic behaviors, evaluating functional vision, and intervention strategies

Dr. Christine Roman presents an overview of Cortical Visual Impairment (CVI), with a look at diagnosis, characteristic behaviors, functional vision evaluation, and strategies for intervention to improve functional vision. CVI is now the leading cause of visual impairment in children.

Download the transcript (Word document).

Transcript

- Introduction

- Early Diagnosis

- Characteristic Behaviors of CVI

- Diagnostic Issues

- Evaluating Functional Vision

- Interventions to Improve Functional Vision

CHAPTER 1 — Introduction

ROMAN: So, people often think that prematurity is the primary cause of cortical visual impairment, but actually, prematurity is just a description of the number of weeks’ gestation you were when you were born. And so prematurity in and of itself is not a cause of CVI.

The things that can happen because of premature birth can be a cause of CVI — so children can have big bleeds, they can have a thing called periventricular leukomalacia, or PVL, they can have things that occur because of prematurity, but prematurity in and of itself is not a cause. Actually, many of the children with CVI are born full term and they have other kinds of causes like pediatric stroke or they may have congenital hydrocephalus, they may have been born with a chromosomal disorder, their mother may have contracted a virus during pregnancy that causes them to have difficulties, they may have had trauma, they may have meningitis.

So things that can affect the brain from prematurity or from things that happen to term babies are causes of CVI. And I should also say that CVI is really the leading cause of visual impairment in children in first-world nations, so anywhere where there is intensive care, high levels of intensive care available to the pediatric population, that’s where we see CVI.

NARRATOR: In a photograph of a neonatal intensive care unit, we see an infant in an incubator being cared for by a female nurse. The nurse holds the infant’s hand and strokes the child’s head. There are many monitoring leads and tubes taped to various parts of the baby’s body.

ROMAN: So today, cortical visual impairment is the leading cause of visual impairment in children by far, and it’s probably going to remain that way.

CHAPTER 2: Early Diagnosis

ROMAN: It’s interesting to me that there are very strict protocols put in place for children who are born prematurely and who may have immature retinas and are at risk for detached retinas. There are also protocols put in place for when children should have their eyes examined, and there are all kinds of recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics about vision care for children.

There is no protocol in place to monitor or identify children with CVI. That’s actually something that I think is not really difficult to do, but I don’t think that kind of pediatric specialists have really concentrated on identifying CVI early. However, when we look at the things that really do help us diagnose CVI, there are three components, and the three components are first, that the child has an eye exam that does not explain the way they see.

So someone examines their eyes, they say the eyes are healthy or possibly they have an eye that turns in or turns out, but it doesn’t explain the fact that the child is sort of acting as though they can’t look at faces or they aren’t interested in books, they aren’t interested in toys, sometimes. So the eye exam doesn’t kind of match the way the child actually uses their vision.

NARRATOR: We see a photograph of an adolescent girl receiving an eye exam from a medical professional using an ophthalmoscope. The tool allows for observation of the retina and other structures of the eye but does not provide a great deal of information about functional vision issues.

ROMAN: The second part is that the child also has a history of some big neurologic event, and that is common to all children with CVI. Sometimes we can’t even identify what happened to the child, but we know from other developmental issues like cerebral palsy or other things that something did happen to this child’s brain.

And the third is that the children with CVI have the presence of these ten characteristic behaviors that are really the identifiable pieces, the part that educators can really assess and evaluate.

CHAPTER 3: Characteristic Behaviors of CVI

NARRATOR: The word “color” appears on the screen.

ROMAN: There really are ten characteristic behaviors that have been identified that pertain to children consistently who have CVI, and those things include an unusual attention to color. Children with CVI often are really drawn to things that have highly saturated color. Red and yellow are the most common colors that people report.

They might not look at the black and white striped cards often used to assess infant vision, but if you show them something they know, like their own red Elmo, they will look at that. Children with CVI might not look at white light, but if you show them a red light, they’ll turn and look. So color is important.

NARRATOR: In a photograph, a bright yellow cheerleader’s pom-pom is displayed against a black background. The word “movement” appears on the screen.

ROMAN: Another one is movement, attention to movement. So children with CVI often begin their visual recovery or their visual journey, if you will, by paying attention to movement. Their dorsal stream vision, that peripheral vision that tells them where things are, is usually active first, so attention to movement. Things that are shiny also seem like they’re moving, and people will report that their child looks at something shiny or they notice a person moving or they notice the fan moving on the ceiling.

NARRATOR: An object like this shiny silver and red pinwheel we see pictured would draw attention both with its movement and color. The word “latency” appears on the screen.

ROMAN: Another one is latency. Children with CVI often have this delay response, so you show them something and it takes a moment. You know, you show it to them, and they look straight ahead or they don’t look, and after some period of moments, they turn and look. So it’s almost like it takes longer for that message to process: latency.

NARRATOR: A video clip shows a young boy in a wheelchair which provides support for his neck and shoulders. He gazes up and to the right as a green plastic ball is held and shaken off to his left. After a few moments, the boy’s eyes track to the left. He sees the ball and smiles.

The word “complexity” appears on the screen.

ROMAN: Another one is complexity, and the difficulty with complexity addresses the ventral stream of vision, or the “what” system, or the development of acuity in the brain. And this is the one in which children with CVI often can’t make sense of things that have lots of patterns, they can’t make sense of things that are against a patterned background, so objects get really lost in the background.

NARRATOR: To illustrate the concept of complexity, a number of small toys have been placed on a background of small black and white squares.

Toys such as a yellow duck and a red car stand out somewhat, but it is much more difficult to distinguish the black and white cow, pinto pony or killer whale figurines when viewed against the background.

ROMAN: If you put it on a black background, they might see it; if you put it against a patterned shirt, it might disappear. And the third part is that children with CVI often can’t look or notice things or use their vision if there’s a lot of competing sensory information. So if someone’s talking or a toy is making music, the child might simply look away.

NARRATOR: An example of complexity in the classroom is shown. Posters with a large number of small illustrations are on the wall. Nearby are two bookcases that are filled with a jumble of colorful toys and games that compete for visual attention.

ROMAN: People have sometimes described children with CVI as looking at the world as though it’s a kaleidoscope of information, that they perceive things through their eyes — their eyes are usually relatively healthy — but they can’t make sense of it. They can’t sort it. One object next to another becomes a non-recognizable object. So that’s complexity, and that’s a very key factor in CVI.

NARRATOR: The words “visual field differences” appear on the screen.

ROMAN: Another characteristic is visual field differences. Very often, children with CVI have damage to the optic radiations which regulate visual fields, and those can be affected, so we assess that to see where they see best. You’ll see a child with CVI who either turns their head a little bit or only notices things on one side, and very commonly, children with CVI have difficulty noticing things in their lower field.

So something drops on the floor and they really don’t know where it is, or if they’re able to walk independently, they might be very concerned about drop-offs — places where there’s a step — or they might miss something on the floor. It’s actually really a safety issue.

NARRATOR: In a photograph, we see dark blue walls that come together in the corner of a classroom. A wide strip of bright yellow plastic that runs along the bottom of the walls clearly distinguishes the walls from the dark green carpeting on the floor.

ROMAN: Some children with CVI use a cane because of this difficulty with lower fields. It’s also important to really recognize that if we present things in the wrong visual field, the child just might not pay attention to it because they don’t see it. They just don’t perceive it. So we really have to assess where they see things best and make sure we position things in those preferred fields.

NARRATOR: The words “visual novelty” appear on the screen.

ROMAN: Another characteristic is difficulties with visual novelty. So this is a very interesting one to me because the human visual system is wired to pay attention to movement and novelty to keep us safe. There’s something moving, our brain says, “Better look, because it could be something dangerous moving toward you.”

And so, too, novelty, that we are wired to pay attention to the most discrepant pattern around us, the most unusual thing that happens, the newest target in the room. So if somebody were to walk in this room right now dressed in a football uniform, I would have to look. My brain would say, “That doesn’t belong. Why is that here?” And it’s not a decision as much as a response, an innate response to just check it out.

But children with CVI see the whole world as novel. All of this mess of pattern and objectness that blends together in a way without meaning creates a situation in which a new target being presented is just more visual white noise. It doesn’t really stand out as new.

NARRATOR: Some strategies employed to eliminate visual white noise and extraneous sensory information are depicted in a photograph. A dark fabric background surrounds a desk on three sides to a height of about two feet higher than the desk’s surface.

On the desk, a red plastic spoon sits on top of a small light box. A symbol card with the word “work” and an illustration of a boy at a desk hangs on the fabric.

ROMAN: So I always share with parents that if you take a child without CVI into a Toys ‘R Us or to a toy store, the child without CVI wants everything they don’t have — they’re very interested in everything new. The child with CVI might only visually attend to something that’s very much like what they already know.

So they respond best to things they’ve seen over and over and over, the familiar thing, not the novel thing. Very important in education because if we don’t know what those familiar things are, we might just be stabbing in the dark, we might be trying so many targets and missing every time. But if we start with the things the child knows and work out from there, we have a much better chance that they’ll use their vision.

NARRATOR: The words “reflex response” appear on the screen.

ROMAN: There are two reflexes that are often different in children with CVI. Children with CVI often don’t blink when you touch them at the bridge of the nose, or they don’t blink in response to visual threat. So we can assess that and just kind of see if that’s also present. So when we look at the visual reflexes, this is the one characteristic that really can’t be added to a child’s program in terms of instruction.

You can’t teach a child to develop a reflex. But we monitor those reflexes over time because the development of those reflexes tend to be paired with improvement in functional vision. So we watch for them as kind of markers of where the child is. However, there is kind of a safety issue related to the visual threat.

If something is moving toward the child’s face and they don’t perceive it in a timely way, it literally could hit their face. So if there’s a beach ball suspended and it’s coming toward the child’s face and they don’t have that reflex, they may actually not protect themselves the way other children would.

NARRATOR: The words “distance viewing” appear on the screen.

ROMAN: Another characteristic is difficulties with distance viewing. So it seems really strange that a child who has essentially a normal eye exam might not notice something across the room, might not notice their favorite object if it’s four feet away from them.

But when you move an object further away, it tends to become more a part of the background array and therefore more complex, so near viewing is often very common in children with CVI.

NARRATOR: A photo of a road running along a side of a building illustrates some of the challenges a child with CVI might encounter. Diagonal yellow lines are painted on a section of the road. Two of those lines run up to vertical yellow posts that designate the sidewalk. In addition, dark shadows alternate with areas of bright sunlight.

The words “light gazing” appear on the screen.

ROMAN: Another characteristic is light gazing. So children with CVI often have this need to really stare at lights, to have more light present. When I look at infants in the neonatal intensive care unit who might be at risk for CVI, one of the things I look at right away is how do they respond to bright light, and the infant should close their eyes defensively to bright light, but the child who we think is at risk for CVI might just open their eyes wide and stare right into the light.

That is not typical. That behavior might persist in children with CVI, and even after they might stop staring at light, they often need more light in order to visually attend. So tablet devices, you know, that have back lighting, light boxes, things that we can pair with light often result in much more visual attention, which is very helpful.

NARRATOR: A bright pink plastic Slinky is looped on top of an illuminated light box. The white light provides contrast for both the shape and the color of the Slinky.

The words “visually directed reach” appear on the screen.

ROMAN: Another characteristic is absence of a visually directed reach. So I talked about there’s this dorsal visual stream and this ventral visual stream. The ability to look and reach as a single action is often dependent upon the integration of those two streams.

And what often happens for children with CVI is you see a behavior in which they look toward a target, literally look away and then reach without looking. And so that’s another one of those traits that we look for that helps confirm that this might be CVI.

I saw a young man last week in a clinic situation, and this young man, even after he could identify the object, simply could not get his hand to where the object was. So that is again really inherent in CVI.

CHAPTER 4: Diagnostic Issues

ROMAN: The three pieces that I talked about– the eye exam that doesn’t explain the way a child sees, the presence, the history of some big neurologic event, and the characteristics associated with CVI — are really kind of the comprehensive way of confirming the presence of CVI. It is not always the way CVI is diagnosed, however. And so because there is no declared protocol in the medical community to identify CVI, some children with CVI are given certain kinds of diagnostic tests that are often associated with children with ocular visual impairment.

It is really considered questionable whether acuity is a construct that is appropriate to use with children with CVI. So someone might actually derive an acuity, but it doesn’t really correlate with how that child uses their vision functionally. Those acuity measures are really associated with children who have eye disorders.

NARRATOR: In a photograph, a young boy is having his eyes examined by a medical technician. The boy’s mother helps to hold the child’s head steady against the chin and forehead rest while the technician operates a device to measure the curvature of the cornea and also any refractive error of the eyes.

This type of device is used to determine the need for corrective lenses, but is not a diagnostic tool for other vision issues.

ROMAN: It’s also sometimes children will be given electro-physiologic tests like the visual evoked potential or the visual evoked response. Those are also not really correlated with how the child sees. So a child might give a certain kind of. There may be a certain kind of outcome to that test, but it doesn’t really tell us how that child sees.

An abnormal VEP does not necessarily tell us with any certainty how that child’s going to use their vision. A normal VEP doesn’t tell us necessarily that that child has normal vision, so it’s a very difficult thing. And finally, there are other kinds of things like the MRI that people will sometimes physicians will ask to have an MRI.

The MRI helps us identify sometimes what happened to the brain, but not all the time. The MRI is good at showing us big structural problems, big bleeds, when big things have changed the structure of the brain. The MRI tells us nothing about the function of the brain. So we would never include the results of an MRI as a way to say a child does or does not have CVI.

So we still have this difficulty, I think, in terms of the medical community when it comes to a consistent way to identify CVI, and therefore the concern is, are all children with CVI in fact being identified? And I think a lot of people feel that we have not identified all the children with CVI. It’s interesting that parents and educators are often people who will make the initial referral.

Parents will persist and say, “I know you told me my child’s eye exam was normal, “but he’s not looking at me, he’s not looking at the ceiling fan.” Teachers will say, educators might say, “I’ve seen many, many children, “and your child’s visual responses are not what I would expect for their age.” So sometimes it’s the persistence of that person going back and saying, you know, “There must be another way to describe what’s happening with my child’s vision.”

So we don’t have this uniform way of identifying children, and so it falls on the shoulders of, unfortunately, parents and educators to really persist in helping children get the diagnosis.

CHAPTER 5: Evaluating Functional Vision

ROMAN: Well, the diagnostic test that is sometimes used is the CVI Range. That functional vision in children with CVI can actually be measured in a stable way using an evaluation tool that I wrote called the CVI Range. And the CVI Range is really used to determine the degree of effect of CVI on a zero to ten scale.

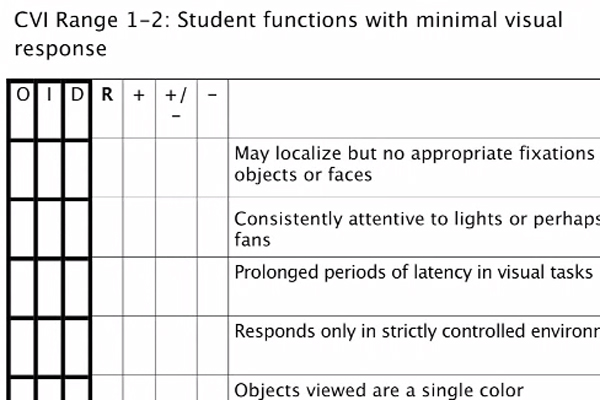

NARRATOR: We see a depiction of the assessment protocol known as the CVI Range for a child with the range of one to two, which is described as a child who functions with minimal visual response.

The assessor is asked to rate the child’s visual response in nine of the characteristic behaviors, such as fixation to objects or faces, attention to lights, latency, movement, and color. To the left of the page are columns to designate whether the rating was based on observation, interview, or direct contact with the child.

ROMAN: That scale is one in which zero represents little or no visual functioning. Ten represents near normal. Almost no child with CVI really gets to ten because that means their vision would be just like other children their age. And because it’s based on the visual behaviors, the development of these visual behaviors through those ten characteristics, it can be used with children who are six months of age through adulthood.

I think it’s mostly used with children who are in school-aged programs through 21. The CVI Range has reliability and validity. It has been studied pretty carefully and has been found to be a stable instrument to actually determine that level. So where you would look at acuity to get levels of eye disorder, the CVI Range looks at levels of function based on those characteristics.

The CVI Range is used not only to determine the level of effect of CVI on a zero to ten scale, but also to use that range, that number, that set of numbers to design interventions. So it is my belief that it’s important not to just pick some CVI intervention and apply it to any child, but rather really diagnostically match the interventions to that assessed level — not above it, not below it — because what we’re really trying to do is to encourage children to use their vision in functional routines, in meaningful activities, but by making adaptations to materials and environments based on that assessed score, we can actually encourage use of vision in a really meaningful way.

So for example, if a child scores, you know, very low on the range, if they score one or two on the CVI Range, I probably wouldn’t present two-dimensional storybooks with complex pictures in it.

NARRATOR: An illustration from the children’s book Sweet Dreams shows a nest with three fluffy owl chicks. The white chicks are visible against the brown nest, but the nest might be hard for a child with CVI to distinguish amid the lattice of branches and leaves in the illustration.

ROMAN: Conversely, if a child scores eight on the CVI Range, I would not have to use those simple, shiny, lighted objects with the child because their vision would have developed to a much higher level.

So what we’re trying to do is really continue to enhance those environments and materials to encourage visual behavior, visual responses, visual attention in meaningful routine activities, and in doing so, help develop more vision in the brain.

CHAPTER 6: Interventions to Improve Functional Vision

ROMAN: So the real expectation is the child moves through the range and that we monitor those changes, we adapt the environments and materials as we see those improvements with the expectation that the child will continually improve their vision. So there’s been, I think, a longstanding belief that children with CVI have improvements in functional vision, but my expectation is that we don’t stop, that we don’t think a little bit of improvement is enough, but that we continue to enhance this ever-improving vision to the place at which a child can have a much, much higher level of functional vision.

I also want to say that in a study that was published from a project that I’m involved in in our clinic setting, in a hospital, that we found that improvement on the CVI Range is not based it has nothing to do with what happened to your brain. So all children with all different kinds of injuries to their brain are all eligible to make significant progress. Children with CVI are expected to improve over time to get to.

My goal is that all children with CVI should get to at least seven on the range, and some children will get as high as nine. Very, very few children get to ten — in fact, I can count on one hand the number of children I’ve seen get to ten. But it’s really dependent upon what we do.

So in the same study that I described to you, we found that no child, regardless of age, that we saw in our clinic setting — and we’ve seen thousands of children there — no child came to us — and when I say “us,” I mean I work in conjunction with a neonatalogist — no child achieved a score higher than three except a few that might have gotten as high as five, regardless of age.

So that’s a nice improvement in functional vision. But when we assess them carefully, establish that score, wrote a plan for intervention, paired those things with functional routines of the day, it’s not a standalone therapy; it’s really a plan for how we can encourage use of vision throughout the day.

We found that 98% of those children got to seven or higher on the range in 3.7 years. And so, it sets the bar pretty high, but we also recognize that when parents bring children to our clinic setting, they are coming voluntarily. These are highly motivated families who are coming from all over the country and sometimes other countries to get this particular service.

The question we ask is if we could find that same level of motivation in educational programs, would we see the same results? In duplications of trainings that I have done in various parts of the country and other countries, we are seeing the same results. And so it seems critical to me that people become educated on identifying children at a very early age so they have the greatest opportunities during the period of greatest visual plasticity, which is young.

We found that even within that 3.7 years for progress into seven or higher on the range that the younger children did it faster; the older children took a little longer. So that early identification is critical.

NARRATOR: In a photograph, we see a very young child being held by his mother as he undergoes a vision evaluation. The tester stands a short distance from the boy and presents a rectangular card with a striped pattern on one end. The boy’s eyes look towards the end of the card with the pattern.

ROMAN: Training of professionals to really understand how to assess children carefully and then how to design programs for them to use their vision in meaningful ways throughout their day is also critical. And then monitoring that and continuing to adjust the program accordingly seems critical to me. There’s just so much on the line, in my mind.

There’s so much on the line because what we have seen over and over is that some of these children who have been thought to have brain injuries that are so severe that people’s expectations for their learning are very low, it’s interesting to see what happens once they have access to their world. And so if a child’s in a wheelchair or a child has no desire to move because they’re not really seeing the world in a very meaningful way, we don’t know what they can learn.

They’re really sort of in a period of deprivation. They’re not getting input from their visual world. And people’s expectations of their. If people have low expectations of children, they might just say, “Well, that’s how these children “that had these really big things happen to their brain, that’s just how they are.”

But what we found was so surprising because we found that in the group of children who do reach this sort of seven and above on the range, we found some of those children learn to read, some of those children learn to use complex communication systems, some of those children can take care of themselves in ways they never could before, some of those children enjoy social activities they could never enjoy before because they now are accessing the world in ways they could not before.

So it really feels to me like there is a lot on the line, and it all starts with identification.

NARRATOR: More information about Cortical Visual Impairment and the CVI Range can be found in the book Cortical Visual Impairment: An Approach to Assessment and Intervention by Christine Roman.

Summary

Diagnosis:

- Normal eye exam

- Big neurologic event

- 10 characteristic behaviors (listed below)

Characteristics of CVI:

- Color: unusual attention to color

- Movement: attention to movement

- Latency: delayed response to visual stimulus

- Complexity: difficulty with visual complexity

- Visual Field Differences: child may notice things on one side more clearly than the other, or in upper or lower field.

- Visual Novelty: child with CVI often prefers looking at things that are familiar

- Reflex Response: often don’t respond when touched on bridge of nose or in response to visual threat

- Distance Viewing: often prefer near viewing

- Light Gazing: drawn to look at light

- Visually-Directed Reach: often unable to look and reach as a single action

Strategies include:

1. Using the child’s preferred color to call attention to something (as with the yellow pompom above).

2. Decreasing visual clutter and thereby minimizing visual complexity

3. Presenting items against a plain black background with clear contrast

For more ideas, see strategies and resources on Paths to Literacy and Cortical Visual Impairment: An Approach to Assessment and Intervention by Dr. Christine Roman-Lantzy.