By Linda Hagood

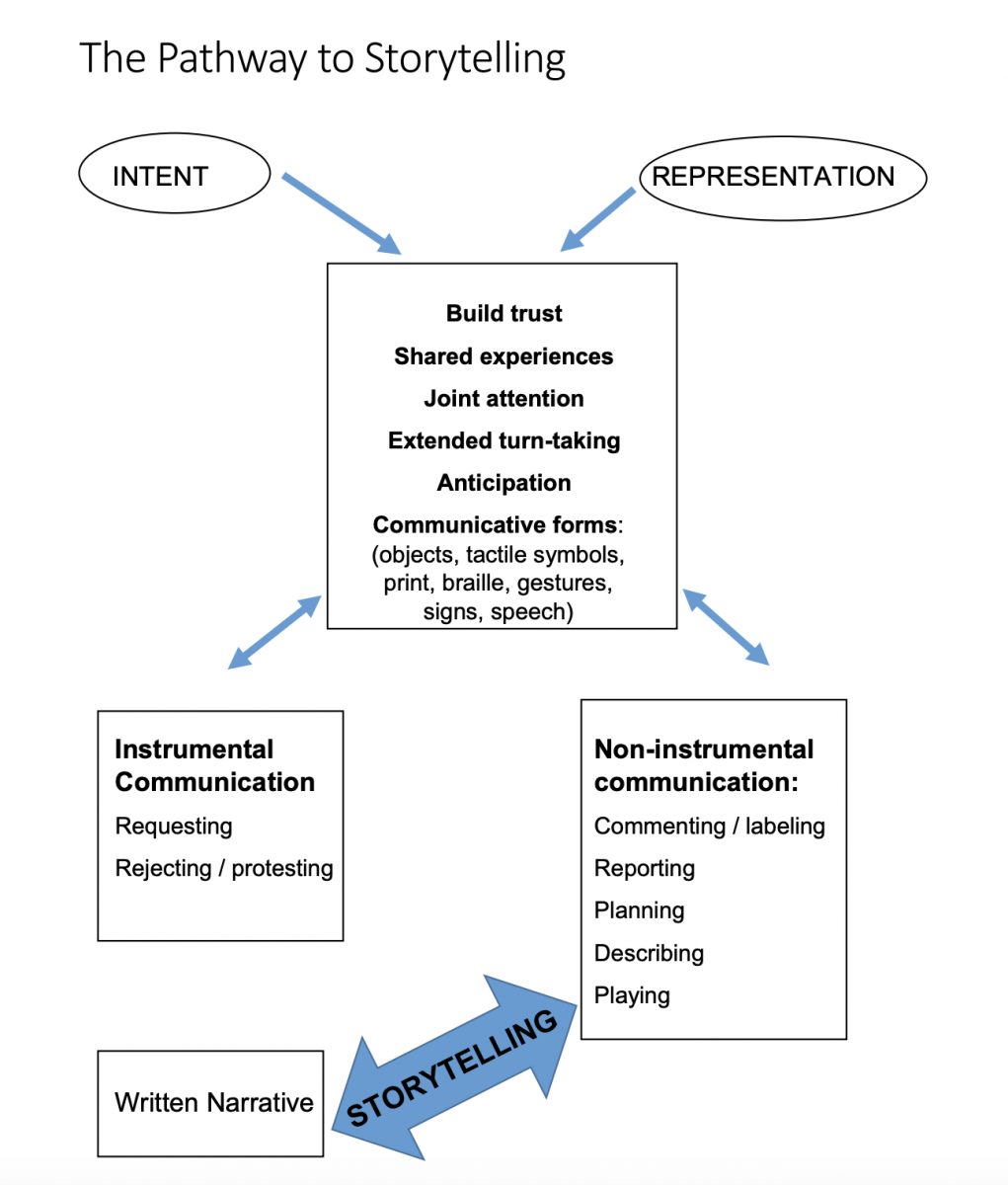

Play-based storytelling is built on a foundation of skills that include both communicative intent and symbolic representation.

Communicative Intent

Communicative intent is the ability to demonstrate a clear communicative purpose for behavior or words. Intentional communication involves orienting toward the partner, persisting in or altering the behavior or words when the partner does not understand, and using the behavior in a variety of settings. Before children are intentional communicators, the partner assumes a great deal of responsibility for interpreting the child’s actions, sounds or words as being intentional. For example, the child may tap his cup on the table, without extending it to the adult, and the adult who knows him well may interpret this as meaning that the child wants more juice. The child may sing a special song, and the adult may interpret the sound as meaning that he wants to sing together. The partner’s “mind-reading” is helpful in building trust, shared experiences, joint attention and extended turntaking.

Symbolic Representation

Symbolic representation is the ability to maintain mental images of non-present objects, actions, or events. Representational skills are closely tied to what we understand, recognize, anticipate, and remember. Children use object, sound, positional, or situational cues to help them learn to anticipate and recognize a routine. They may begin by recognizing and anticipating a part of a familiar activity, such as peek-a-boo or “falling down” games like Ring Around the Rosie. Later, they may use object (the blanket for peek-a-boo, the washcloth for bath time) or sound cues (the Ring around the Rosie song) to anticipate the whole routine, even when the cues are presented before the activity begins. These are important first steps to understanding pictures, braille, print, signs or speech.

Instrumental Communication

Once these important foundations are established, two purposes for communication are established. We often begin with instrumental communication to meet one’s own needs by requesting or protesting/ rejecting. While this function for communication is very important, it does not lead us very directly to storytelling or conversation. Often, interactions with children who only communicate instrumentally are limited to single turns, although it is certainly possible to arrange interactions so that students have multiple opportunities to request or choose. More importantly, the partners of children who use language only for requesting often feel that their relationship with the child is very limited and that they only serve as a provider of objects or activities for the child.

Non-Instrumental Communication

It is also important to model and teach the child to use non-instrumental communication for purposes such as commenting on or labeling objects, actions, people, and places; reporting on or planning activities; describing and playing. These functions are more closely tied to both conversation and storytelling. When using these non-instrumental communicative functions, we are communicating to share information and experiences, not simply to prompt the child to request or choose.

Storytelling

Eventually, the child is ready to begin storytelling, which involves communicating to sequence events, with a clear beginning, middle, and end. Storytelling can include both retelling of experience stories or personal narratives and telling of pretend or sensory stories. Bruner (1986) described storytelling as a “contextual bridge between playing and written narrative,” and the diagram shows that it is a bridge that goes both ways. As the story is co-created and documented in written narrative, the child’s non-instrumental communication skills also improve.

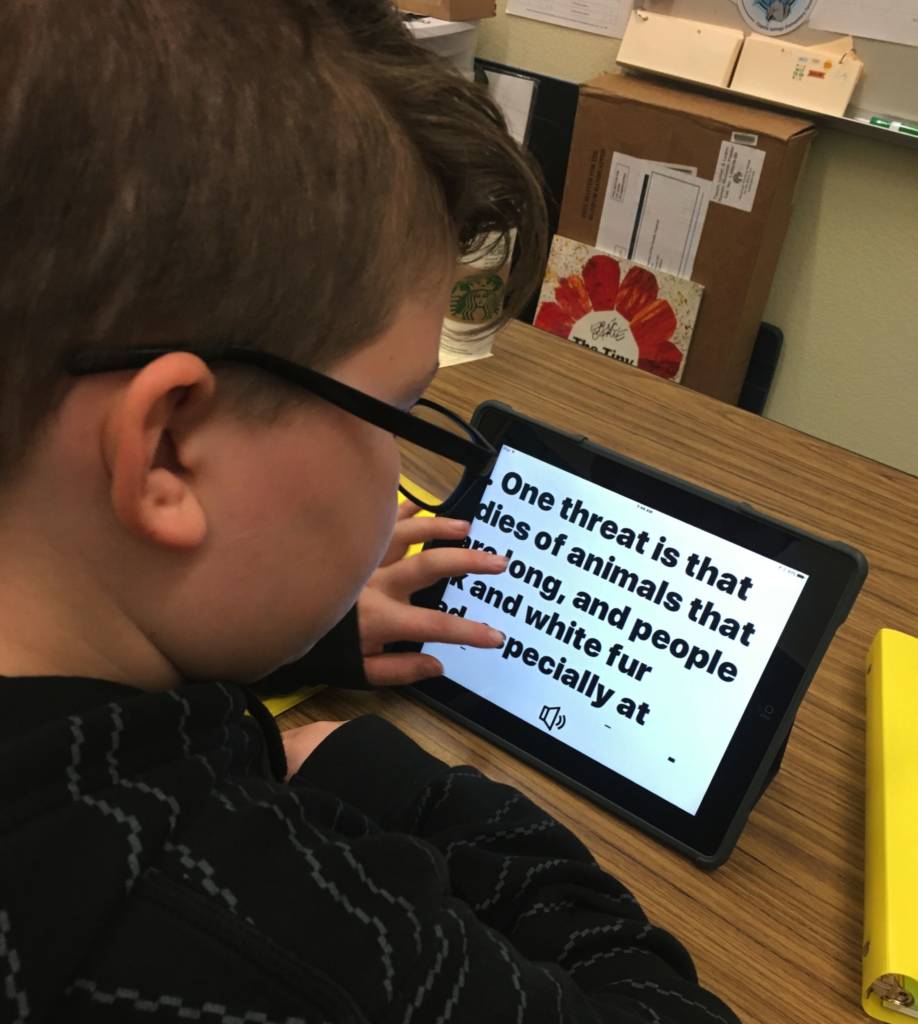

Note that a child/student can participate in storytelling at any point along this graphic, even if they do not yet utilize more sophisticated communication forms and functions. Sometimes folks get stuck on a first, then, next process and then the kids never get access to even receiving stories and pretend in the first place. For example, a student who is pre-linguistic might giggle when the adult does something that is ridiculous or pretend and clearly understand that the adult was joking, even if they are pre-linguistic and do not express functions formally outside of requesting and rejecting. Many pre-linguitstic students still value stories and play – they just have to find a partner who liked their topics too and can act them out.

Return to Playing with Words homepage.