By Linda Hagood

When assessing and planning Playing with Words activities, I’ve found it helpful to use developmental play levels, first suggested by Piaget (1926) and expanded by the work of Garvey (1977), Smith & Volstedt, 1985, and Wolfberg (2003). Play can be thought of in terms of both social and symbolic dimensions, as shown in these tables (adapted from Better Together, Hagood, 2008)

Social Play Level |

Playing with Words example |

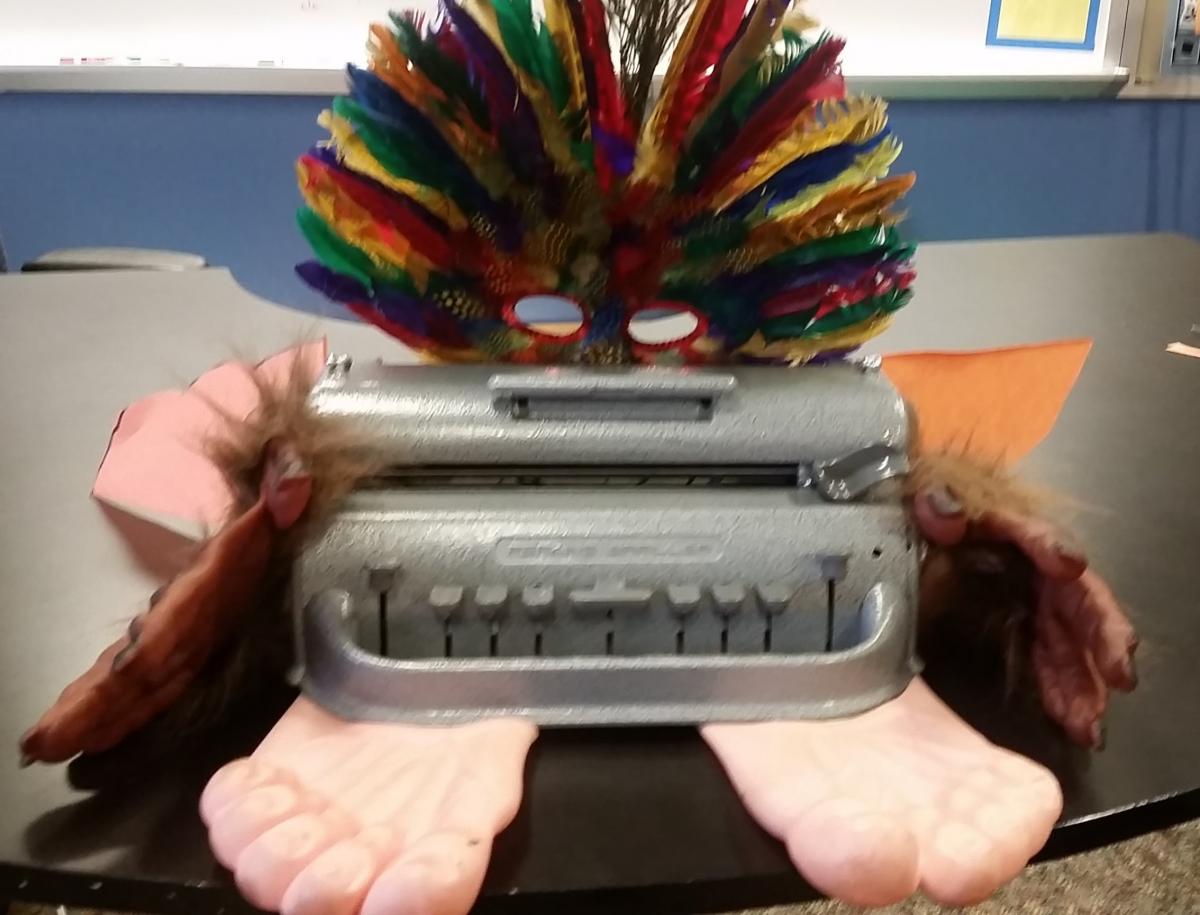

| Isolated/ solitary play without reference to partners or others in immediate area; with or without objects or toys | Scribbling with brailler or marker, or engaging in self-talk about favorite topic; no concern about communicating thoughts to others |

| Parallel playing in a side-by-side manner, using similar or matching materials, some simultaneous imitation occurs.

|

Adult or peer begins to play beside student, imitating and expanding on actions or words modeled by the student, or scribbling with a second brailler or markers; student may occasionally reference partner by touching, imitating adult , or glancing briefly at objects.

|

| Cooperative early playing together, characterized by sharing, turn-taking, role assignment, usually unplanned and loosely structured | Works together with partner(s) to develop a story that includes everyone’s ideas. Story creation has an additive quality, with one partner adding an idea which was inspired by the previous one (“yes, and…”). Partner’s ideas are appreciated and help student to think of or add to original idea. Story follows a stream-of-consciousness format with no real plot or outcomes in mind. Character assignments may shift throughout the session. |

| Collaborative playing together in a planned and coordinated way, usually with well-established roles and defined goals. | Story is planned as a group, with considerations of strengths of individual group members (e.g., scribe/typist/braillist, proofreader, brainstormers, set designer, script markers). Characters are assigned by group and usually remain fixed throughout storytelling. |

Symbolic (Cognitive) Play Level |

Playing with Words Example |

| Sensorimotor play that focuses on actions, sounds, visual stimulation or tactual experiences (e.g. play in sand, clay, with spinning tops or keyboards, iPad apps that have sensory appeal) |

Scribbling with brailler, experimenting with soft and light touch or creating rhythms, sound effects, repeated chant, song or verses in story line

|

| Early pretend (preoperational): Brief episodes of unconnected representational play (e.g., using a stick as a light saber, pretending to drink from empty cup) |

|

| Later pretend (preoperational): Play that involves enacting connected events with loosely defined, shifting roles. |

|

| Rule-based (early concrete operations): Play with clear rules and role definitions (e.g. card games, playground games, highly structured dramatic play) | Storytelling involves original, but standardized plot lines, routinized sequencing, stereotyped beginnings (“once upon a time”) and endings (happy!), universal themes (e.g. good vs. evil); beginning to brainstorm plots before beginning to write. |

|

Strategy-based (later concrete operations to formal operations): Play may be competitive or collaborative, involves foresight and planning (e.g. chess, sports, dramatic magic or comedy shows)

|

Storytelling may involve humor, multiple plot lines, surprise endings, and mystery. Use of graphic organizers, outlines and color-coding helps to plan story sequence and outcome. |

References:

Garvey, C. (1977). Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hagood, L. (2008). Better Together: Building relationships with people who have visual impairment and autism spectrum disorder (or atypical social development). Austin, TX: Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Piaget, J. (1926). The Language and Thought of the Child. New York: Harcourt.

Smith, P.K. & Vollstedt, R. (1985). On defining play: An empirical study of the relationship between play and various play criteria. Child Development, 56, 1042–1050.

Wolfberg, P.J. (2003). Peer Play and the Autism Spectrum: The Art of Guiding Children’s Socialization and Imagination. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger’s Publishing Company.

Return to Playing with Words Introduction and Essential Components.

- Why Is It Important?

- Reflections by Students

- The Importance of Storytelling and Story Creation

- What Do We Mean by “Play”?

- Parallels Between Social & Symbolic Play and Playing with Words

- Differences Between Social Stories and “Playing with Words” Stories