Definitions of literacy have expanded to include auditory skills as a valued form of literacy. While it is important for all students to develop strong auditory strategies, this area is crucial for those who are blind or visually impaired.

For more information on educational strategies specific to the needs of students with a hearing loss, please see the Deafblind section.

Is Listening Literacy?

There has been some controversy in the past about whether or not accessing text through hearing is actually reading. Dr. Phil Hatlen gives his thoughts about this in Literacy According to Phil. As more auditory formats such as podcasts and audiobooks become mainstream, it has become clear that whether or not listening to information is the exact same as reading print or braille, this is an important literacy format. In their educational programs, many students with visual impairments will need to access a significant amount of information from text through auditory means. As the skills to do this are different from those used for listening in casual conversation, auditory strategies are an important component of literacy instruction.

Should listening skills be included in literacy instruction?

Students who are blind or visually impaired must be provided with adequate instructional support that equips them to interpret auditory materials efficiently and effectively. Literacy includes many auditory elements, from the importance of sound play and phonemic awareness in early literacy development to more sophisticated use of listening to learn from classroom instruction. Students may need to learn to listen so that they can listen to learn. Lizbeth Barclay and Jodi Floyd have suggestions on how to integrate teaching students with visual impairments to develop listening skills within literacy instruction. It is important to remember that merely providing materials in audio format or reading aloud written text does not ensure literacy.

In their article Effective Classroom Adaptations for Students with Visual Impairments, authors Penny R. Cox and Mary K. Dykes caution that while auditory input provides another way that students can gain information, “teachers should not assume…that students will understand verbal input in the same way and at the same depth as other students understand visual input. Auditory language triggers the creation of mental images that correspond with words. Images are recalled to assist students in comprehending verbal language (Barraga & Erin, 1992). A student with visual impairments is likely to have fewer and less detailed mental images to correspond with verbal language. Such images may differ according to a student’s individual experiences and verbal input he or she has received from others (Whitmore & Maker, 1985).”

What specific auditory skills may be affected when a student has a visual impairment?

There are many skills involving the use of the auditory system that all children develop, often with no intervention. An inventory of listening skills may help isolate areas of difficulty for a student. The following is a sampling of skills that may be impacted by a visual impairment and how they relate to the Expanded Core Curriculum:

- Locating and identifying sound sources (Sensory Efficiency)

- Turning to face the person who is speaking (Social Skills)

- Listening comprehension (Compensatory Skills, concept development)

- Use of audio assisted reading (AT, Compensatory Skills)

- Using a screen reader to scan a reference for keywords (AT)

- Taking notes during a lecture (Compensatory skills, study skills)

- Listening skills, such as listening for approaching vehicles, and auditory object perception, for safe mobility (O&M)

- Use of a reader – how to find, pay, and benefit from this assistance (Self-Determination)

What is the difference between auditory, hearing, and listening skills?

Auditory topics cover a broad range. Questions about a student’s hearing, whether their auditory system is working properly, at what frequencies and in what conditions, as well as issues related to prescriptions for hearing aids, for instance, are best addressed by personnel in the medical field, such as by an audiologist. Using informal tools, VI professionals and family members can be helpful partners by sharing information with medical practitioners on how the student functions outside the clinical environment, so they can make informed decisions about these often atypical patients. Listening skills, how the student interprets and uses what is heard, are more often assessed and addressed in the realm of educational intervention. The fact that a child can hear a radio nearby does not mean that they can understand the information being aired on the station. A child can hear the teacher speaking but not realize that her tone of voice indicates that attention must be given to her directions. Words can be heard but not understood. When a visual impairment limits access to distance information, optimal use of listening skills can make a big difference, both for educational performance and safe mobility.

Learn more about the importance of hearing assessment.

What is Central Auditory Processing Disorder and Why Is It Important?

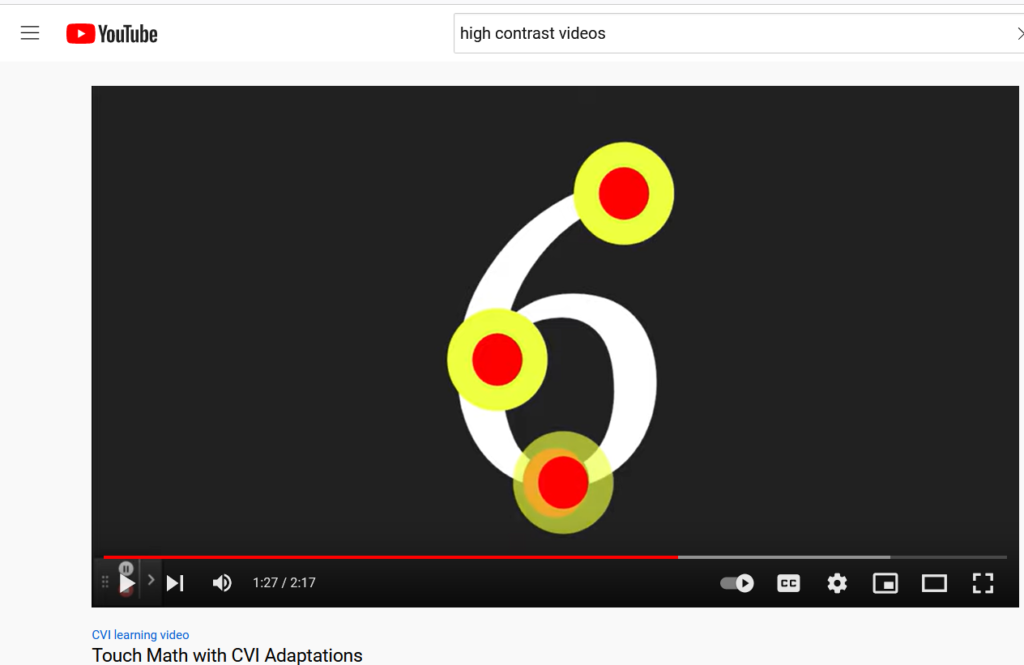

It is said that central auditory processing disorder is to hearing what cerebral visual impairment or CVI is to vision. Central auditory processing disorder (CAPD) is defined as deficits in the neural processing of auditory information in the central auditory nervous system (ASHA, 2019). Central auditory processing disorder is also called auditory processing disorder (APD), cortical deafness, and central deafness. In these definitions, “central” refers to the site of the problem with hearing and comprehension. While the peripheral hearing system includes the outer, middle, and inner ear to the auditory nerve, the central hearing system refers to the area from the brainstem to the brain. With CAPD, the ears may be functioning normally but sound is not reaching the brain in a way that is meaningful. Read more about this topic.

Who evaluates a student’s auditory skills?

Students who are blind or visually impaired rely heavily upon their hearing, and should have their hearing assessed on a regular basis by professionals such as audiologists. If a student has a hearing loss in addition to a visual impairment, it is important that instructional approaches accommodate appropriately for both sensory systems. There are many informal hearing screening tools, including two that have been developed for students with visual impairment:

- IFHE (Informal Functional Hearing Evaluation) – an informal evaluation designed to guide a Teacher of the Deaf/Hard of Hearing (TDHH), Teacher of the Deafblind (TDB), Teacher of Students who are Visually Impaired (TVI), Speech Pathologist, or Educational Audiologist in determining the impact of a potential hearing loss on educational functioning for students with visual impairments and multiple disabilities

- Sound Travels – a tool to assist the team to evaluate the sound environment related to mobility

These tools are helpful to strengthen collaboration with a teacher of the deaf and hard of hearing and/or an audiologist, by sharing specific information on how the hearing of a student with a visual impairment is functioning outside the clinical setting. This is especially important for travel (orientation and mobility), as well as adaptations both at home and school. For more information, see The Importance of Hearing Assessment.

How can families help their young children develop listening skills?

Learning to listen efficiently starts at birth and literacy skills are useful all day long. Listening activities may be built into family routines, as well as story time, games, and other activities. Barclay suggests approaches for families and educators to help develop early listening skills in young children with visual impairments. Parents can boost their child’s learning by using the tips assembled by Jim Durkel.

Additional Resources

Using Oral Traditions to Improve Verbal and Listening Skills by Joanne R. Pompano, Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute