Recently I had yet another conversation with a distraught parent from another state, who was upset that her child who has cortical visual impairment (CVI) was not being included in the story/circle time at preschool. “He doesn’t need to see the pictures,” the parent was told.

Recently I had yet another conversation with a distraught parent from another state, who was upset that her child who has cortical visual impairment (CVI) was not being included in the story/circle time at preschool. “He doesn’t need to see the pictures,” the parent was told.

As a Teacher of the Visually Impaired (TVI), it is my job to help educational teams find ways to make all activities accessible, as well as educate everyone about why it is SO critically important that children with CVI or other visual impairments, be fully included and have access to these very important, daily activities in the classroom.

When was the last time you read a story to a 4-year-old child? If you imagine that scenario, it likely includes a picture book. Now imagine reading a book to a 4 year old and refusing to allow him or her to look at the pictures as you read. This would surely be a short-lived activity!

Why do young children need these illustrations to stay focused and interested in the story? Why is it that books for young children are so richly illustrated?

For young children, words are important, of course, but the real world (or a representation of it through pictures) is what they crave, because real world interaction is what they need to grow, learn and develop vocabularies rooted in meaning. Stripping away pictures from their books demonstrates very quickly how much young children need the pictures to anchor them to the words being read.

Empty Language

Children who have CVI or other visual impairments have a much greater chance of developing “empty language” than their sighted peers; that is, vocabularies that are not rooted in meaning. “Empty language refers to a situation of confusion where the blind or visually impaired child has words to talk about something, but incorrect or no ideas to attach to the words.” (Anne McComiskey, Family Connect, American Foundation for the Blind). With less visual input, reduced shared visual attention, and fewer chances to interact with their environment, they may have poorer vocabularies and use “empty words.”

Consider this story to illustrate empty (or incorrect) language:

Carlos is a four year old, who has been blind from birth. He attends a preschool program located within a public school building and fire drills are a common occurrence. The shrieking siren is extremely loud. Carlos’s team tells me he absolutely hates fire drills, covers his ears and cries throughout them. They have a hard time calming him down afterward.

Carlos is a four year old, who has been blind from birth. He attends a preschool program located within a public school building and fire drills are a common occurrence. The shrieking siren is extremely loud. Carlos’s team tells me he absolutely hates fire drills, covers his ears and cries throughout them. They have a hard time calming him down afterward.

One day, I was visiting him on a fire drill day. I tried to prepare Carlos in advance, by talking to him about it and warning him that one was coming soon. It did not help. He covered his ears, burst into tears and was inconsolable for some time after it was over.

When he calmed down a bit, and I could talk with him, I asked him about the fire drill, hoping to get him to express his thoughts and feelings. “I HATE fire!” he told me, through jagged breaths.

Then, it struck me. Empty language?

I asked him, “Carlos, what is fire?”

He put his hands to his ears and told me “Fire is so loud.”

Carlos had assumed that the siren sound itself was “fire.” Due to his vision loss, he had no direct experience with fire and had assumed (with good reason) that fire was the obnoxious sound. Think about it from his perspective: every time that horribly loud noise came blaring through the school speakers, the word he always heard associated with it was “fire.”

Sadly, I did not have any magic strategies to help him cope with the drills, but we could at least help him learn the difference between fire and the fire drill siren.

With empty language, children can frequently ‘talk a good game.’ Telling us that he hated fire sounded perfectly reasonable from a four year old perspective. But it was only though probing his thinking that we could discern his “empty” or incorrect language.

In children with CVI, empty language is also common. They may look at images or scenes but not be able to decipher or make sense of what they see. Meanwhile they hear language swirling around them. When the two don’t connect, the situation is ripe for the development of empty language.

Strategies: What can we do to prevent empty language?

- Name the item that the child is looking at – keep it simple at first! “Cat, you see the kitty cat!”

- Repetition is how all children learn language. Children with vision impairment including CVI need repetition as well, probably even more, due to processing delays and lack of experience. An adult may feel they repeat things millions of times, but it is not wasted effort.

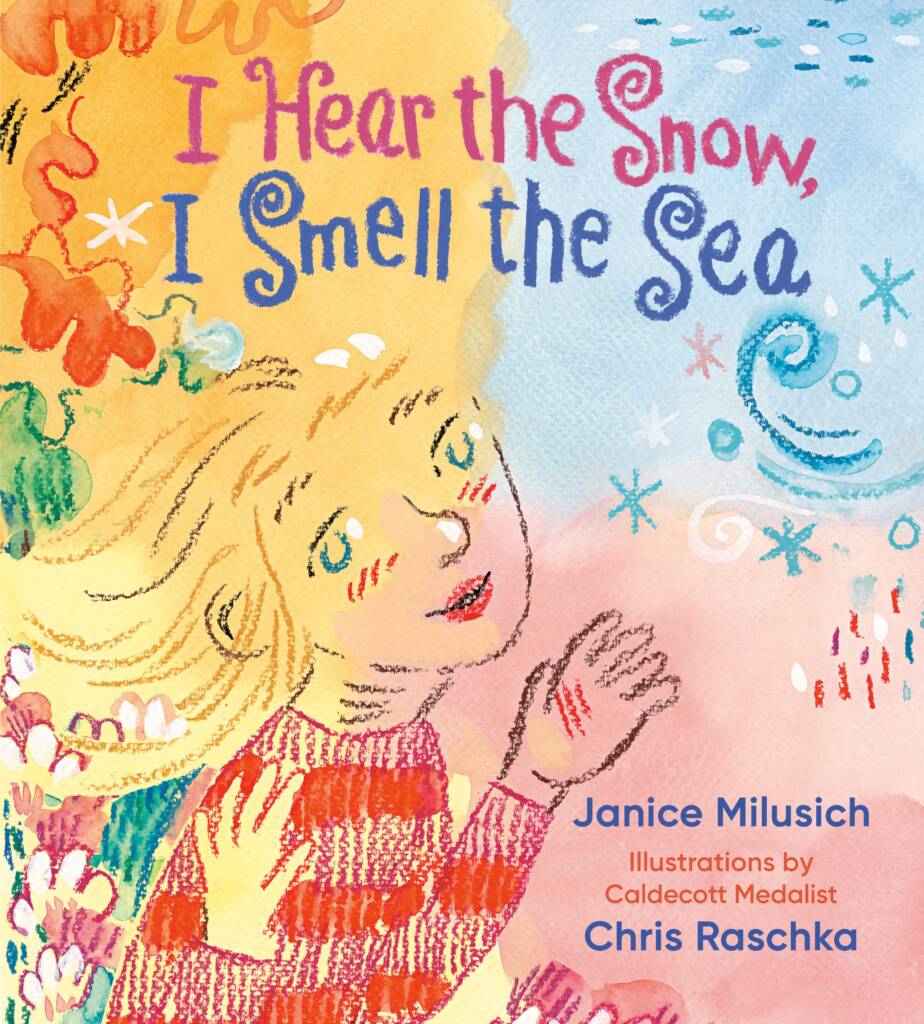

- Story time: Too often, children with CVI are plopped down to listen to stories in preschool programs, while their sighted peers have the benefit of seeing the pictures. We are doing a double disservice to these young children if we do not make the pictures accessible and available to them.

But how?

- Bring one or two of the central themes to the child. For example, for a book about a little girl and a pumpkin, bring a real pumpkin and a life-like doll to the child. Support as they explore the objects with hands and eyes as the story is read.

- Use an iPad. For children who are able to understand and process pictures, take pictures of the book’s contents before the story is read. Show the child the pictures using back lighting, zoom in to reduce visual complexity, and expand function to their benefit.

- If the pictures from the book are too complex, showing these to a child who cannot process them is not helpful. If the story is about a cow, and the child has shown the ability to understand simple clear photographs, call up a simple picture of a cow and use that instead of the pictures from the book.

Reprinted with permission of the author and Start Seeing CVI.