By Eva Lavigne and Ann Adkins, TSBVI Outreach

Parents and teachers of students with visual impairments often have questions about how the choice is made regarding a student’s literacy medium. They express concerns about whether a student should be primarily a print reader or a braille reader, and want to know how and when decisions about reading media are made. Dr. Phil Hatlen, Superintendent of the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, addressed this issue in a previous article, and stressed the importance of the Learning Media Assessment (LMA) and the role of the teacher of the visually impaired. While the definition and purpose of the LMA are clearly defined by State Board of Education (SBOE) rules and the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), a definition of literacy is not always easily understood, especially for visually impaired students.

What is the Learning Media Assessment (LMA)?

A learning media assessment is mandated in the State Board of Education Rules for each student who is referred for an initial evaluation to determine eligibility as visually impaired. It is also required every three years as part of the reevaluation process to maintain eligibility. Best practices indicate that the learning media assessment should be an ongoing process and it should be updated as often as needed, sometimes annually for very young students or those whose needs and abilities change.

All students who are referred for evaluation or reevaluation to determine eligibility as visually impaired must receive a learning media assessment conducted by a certified teacher of students with visual impairments. It must include:

- Recommendations for the use of visual, tactual, and auditory learning media.

- A recommendation for ongoing assessment when it is needed.

- A determination of the student’s primary learning medium to decide whether the student is functionally blind.

The LMA gathers three types of information on each student:

- The efficiency with which the student gathers information from various sensory channels: visual, tactual, and auditory

- The types of general learning media the student uses, or will use, to accomplish learning tasks

- The literacy media the student will use for reading and writing

The LMA focuses on two phases:

- The selection of the initial literacy medium (this phase begins at infancy and continues through the beginning of formal literacy instruction).

- The continuing assessment of literacy media (this continues throughout the student’s school years).

The learning media assessment is “an objective process of systematically selecting learning and literacy media” (Koenig and Holbrook). This includes the total range of instructional media needed to facilitate learning, and is understandably different for each student. It consists of general learning media (instructional materials and methods) and literacy media (the tools for reading and writing). Instructional materials can include a range of options, such as pictures, real objects, tactile symbols, videos, worksheets, tapes, and augmentative communication devices. Methods can involve modeling, demonstrating, prompting, questioning, pointing, and lecturing. The wide range of possible materials and methods provides for students at all ability levels. The scope and definition of literacy media is more complicated, however. The “tools for reading and writing” generate concerns about print and braille, prompting many questions about literacy for visually impaired students.

What is “literacy”? What does literacy mean for a visually impaired student?

Most people acknowledge that literacy has something to do with reading and writing. Many recognize the importance of literacy in order to be “an educated person” and realize that success in school and employment are fundamentally linked to the attainment of literacy skills. Braille literacy is directly addressed in the 1997 amendment to the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA). In developing the IEP (Individual Education Plan), the ARD committee must:

& in the case of a child who is blind or visually impaired, provide for instruction in braille and the use of braille unless the IEP team determines, after an evaluation of the child’s reading and writing skills, needs, and appropriate reading and writing media (including an evaluation of the child’s future needs for instruction in braille or the use of braille), that instruction in braille or the use of braille is not appropriate for the child. [IDEA Section 1414(d)(3)(B)(iii)]

Literacy, however, is more than just legal terminology and involves more than the ability to read and write in braille. The following definition reveals the role literacy plays in everyday life:

“Literacy is the ability to read and write at a level that would enable an individual to meet daily living needs. Literacy is a continuum from basic reading and writing skills all the way up to various technical literacies. It is different for different people, in distinct times and various places.” (Marjorie Troughton, One is Fun, 1992)

This definition indicates the importance of looking at the student individually along a literacy continuum and the value of re-examining literacy needs and skills as the student progresses. Many VI students need an array of literacy tools and perhaps several literacy media to be successful in school. For example, a student might use braille for note taking, speech output for the computer, audiotapes or a scanner for reading novels, and print for math. Students learn and develop as individuals, not as a group. Their needs may change as they become older and as they approach tasks beyond the school environment. It is important to identify the medium/media which most benefits each student. For example:

- Some students may benefit most from using print.

- Some students may benefit from using uncontracted braille.

- Some students may benefit from using contracted braille.

- Some students may benefit from using both print and braille.

- Some students may not be able to benefit from either braille or print, and may primarily use an auditory medium, tactile symbols, real objects, or other tactual media.

The degree to which a given student uses a specific medium will be influenced by many factors: age, general ability, visual and tactual functioning, visual prognosis, motivation, academic/nonacademic demands, environmental conditions, personal and interpersonal factors (such as an acceptance of one’s blindness), reaction to societal attitudes about blindness, and/or a lack of exposure to braille (Caton, APH, 1991). Each student with a visual impairment has a unique personal journey to literacy that should include all the necessary literacy tools and media to meet school and daily living needs. It may take an extended period of time for a visually impaired student to master the multimedia he or she will be required to use. Planning and preparing for a student’s literacy needs throughout his life is a challenging yet important task.

How are these decisions about literacy made? How does the LMA indicate which students might benefit from using print and which might benefit from using braille?

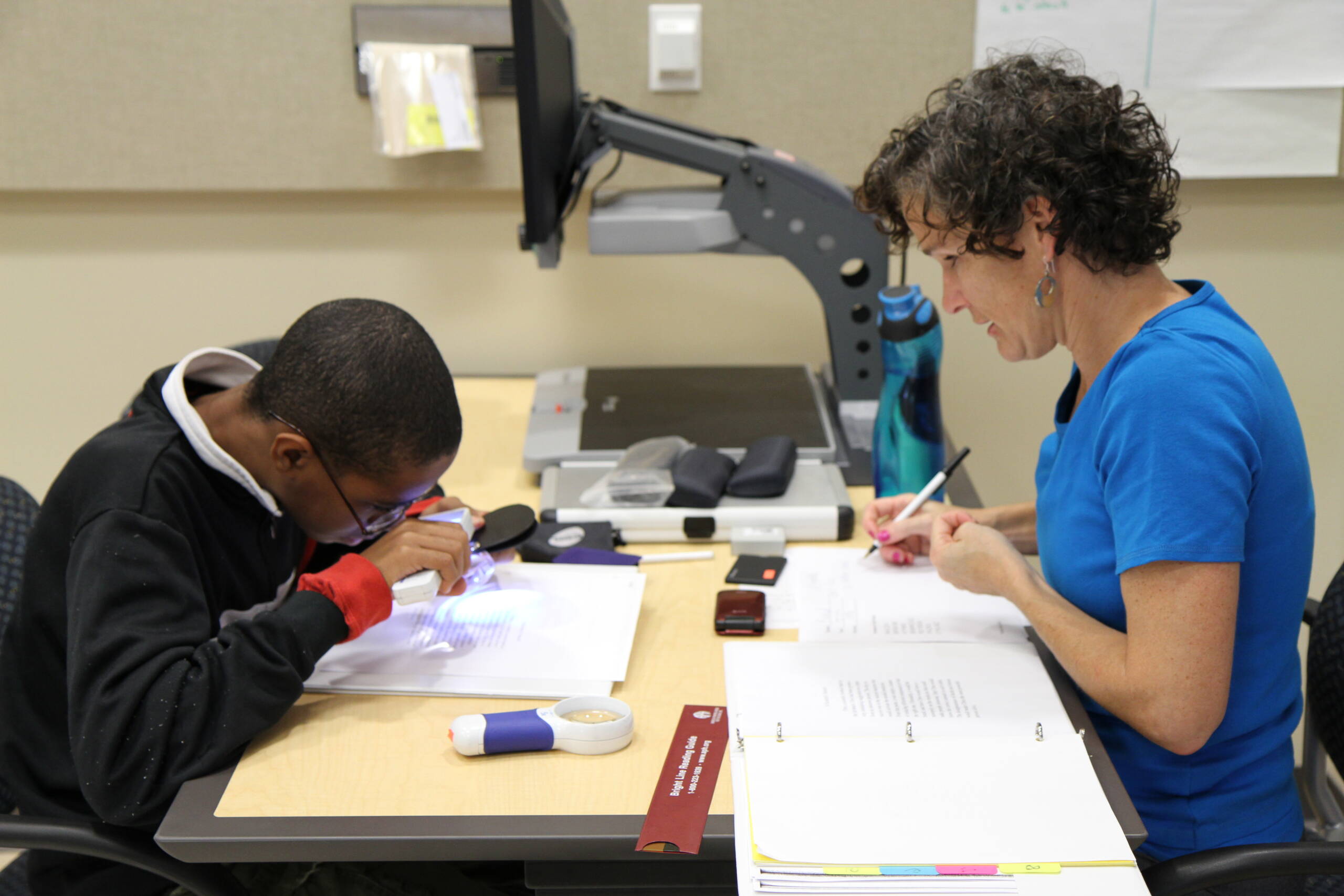

It is clear that decisions about literacy media are to be made based on the assessed needs of the student and not on other factors such as the availability of a teacher of the visually impaired, financial considerations, convenience, or any other outside factor. The learning media assessment is a process of gathering objective information to provide a basis for selecting appropriate learning and literacy media for blind and visually impaired students. Objective data is collected from many different observations and is used to make decisions about the student’s learning and literacy needs. Parents are key members of the educational team, and parent observations and parent interviews provide valuable information to include in the decision-making process. It is important for teachers and parents to work together to gather information, increasing the accuracy and effectiveness of the LMA. Results of the LMA guide instructional planning and programming to insure that each student gains literacy skills in a medium or media (print and/or braille) and develops an array of literacy tools to meet school and daily living needs.

A valuable reference to help with making these decisions is a publication entitled Learning Media Assessment of Students with Visual Impairments: A Resource Guide for Teachers, by Alan Koenig and Cay Holbrook (1995). It provides a process and rationale for conducting learning media assessments, and has a variety of forms for gathering objective data. This text also reveals the characteristics of students who might be likely candidates for a print or a braille reading program (page 43):

Characteristics of a Student Who Might Be a Candidate for a Print Reading Program:

- Uses vision efficiently to complete tasks at near distances (reaches for object on visual cue, explores toy or object visually, discriminates likenesses and differences in object or toy visually, identifies object visually, etc.)

- Shows interest in pictures and demonstrates the ability to identify pictures and/or elements within pictures.

- Identifies name in print and/or understands that print has meaning.

- Uses print to accomplish other prerequisite reading skills.

- Has a stable eye condition.

- Has an intact central visual field.

- Shows steady progress in learning to use her vision as necessary to assure efficient print reading.

- Is free of additional disabilities that would interfere with progress in a conventional reading program.

Characteristics of a Student Who Might be a Candidate for a Braille Reading Program:

- Shows preference for exploring the environment tactually (explores object or toy tactually, uses tactual means to travel and explore the environment, etc.).

- Efficiently uses the tactual sense to identify small objects.

- Identifies her name in braille and/or understands that braille has meaning.

- Uses braille to accomplish other prerequisite reading skills.

- Has an unstable eye condition or poor prognosis for retaining current level of vision in the near future.

- Has a reduced or nonfunctional central field to the extent that print reading is expected to be inefficient.

- Shows steady progress in developing tactual skills necessary for efficient braille reading.

- Is free of additional disabilities that would interfere with progress in a conventional reading program in braille.

Other Factors to Consider in Determining a Student’s Literacy Medium/Media:

Debra Sewell, of TSBVI, lists these considerations:

- School requirements:

- Can the student “keep up” with peers?

- How much time is spent completing homework?

- How much energy is spent completing work?

- Is the workload being reduced?

- Is there enough practice with meaningful text? (extended reading, not just line by line reading, such as on worksheets)

- Are the skills adequate for the future?

- Are there (diagnosed or undiagnosed) reading problems?

- Are there neurological issues? (such as reduced fine motor skills, etc).

- What is the availability and use of optical devices?

- What is the portability of optical devices?

- Is the student motivated to learn?

What is the Continuing Assessment phase of the LMA?

In the continuing assessment phase of the LMA, the educational team will consider the appropriateness of the initial decisions and examine the student’s need to develop new literacy skills. The continuing assessment phase annually collects and examines:

- The results of any new medical information to determine if there has been a change in visual functioning since the last review

- Reading rates and reading grade levels, to determine whether the student reads with sufficient efficiency to perform academic tasks successfully

- Academic achievement, to determine whether or not the student is making academic progress in the current medium

- Handwriting skills, to determine whether or not the student is able to read his or her own handwriting and whether or not the handwriting is legible to others

- The effectiveness of the student’s existing array of literacy tools, to determine whether instruction is needed in additional literacy tools to meet current or future literacy needs

- Diagnostic teaching allows for ongoing assessment of the appropriateness of the initial decision about literacy. If a student is not making adequate progress, the educational team might consider adding supplementary literacy tools or changing the primary literacy medium. Additional instruction may be needed in new methods or the use of new materials. Diagnostic teaching will continue to evaluate the student’s efficiency with literacy tasks.

Conclusion

It should be evident that the determination of a student’s literacy medium/media is not an “either/or” decision. Nor is it a final one. Students change, as do their needs for different types of information. More and more visually impaired students are realizing the benefits of using both print and braille, and many supplement their reading with auditory information. Supplementary literacy tools, such as E-books, are helpful as students approach tasks requiring increased reading and writing skills in higher education. All students need access to a variety of literacy tools. This is no less true for visually impaired students.

References:

Caton, Hilda, Ed. (1991). Print and Braille Literacy: Selecting Appropriate Learning Media. American Printing House for the Blind.

Koenig, Alan J. and Holbrook, M. Cay. (1995). Learning Media Assessment of Students with Visual Impairments: A Resource Guide for Teachers. Austin: Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Sewell, Debra. Workshop Presentation, “The Fine Line Between Print and Braille”. Austin: Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Troughton, Marjorie. (1992). One is Fun: Guidelines for Better Braille Literacy. Ontario: Canadian National Institute for the Blind.

This article was originally published by Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired (in the Spring 2003 SEE/HEAR Newsletter) and is reprinted here with permission.