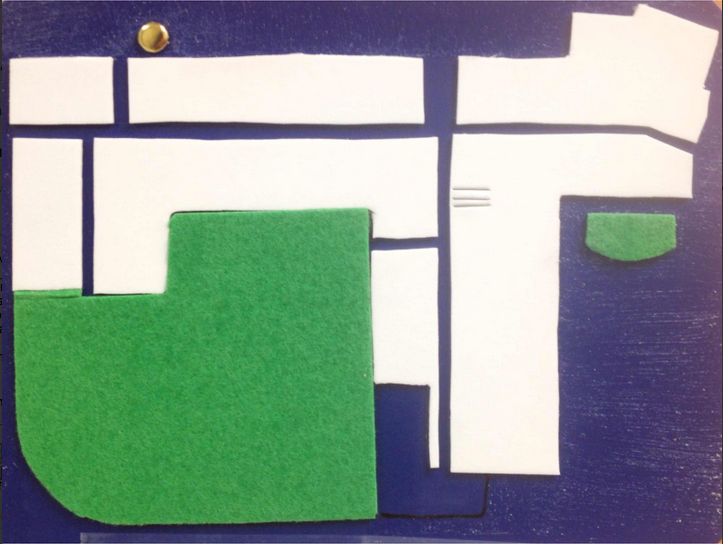

Skills in reading/writing tactile images, or “tactile-graphicity,” develop with lots and lots of carefully sequenced, guided exposure to thoughtfully designed and well-made tactile images. It takes time, strategy, and a steady hand to create tactile maps, but particularly as a dually certified TVI/O&M specialist, I’m completely committed to the process. Why? There’s a danger for concepts of tactile learners to be incomplete, inaccurate, and un-integrated. Tactile maps and other tactile images can be used to address this in the following ways. Learner’s concepts can become more complete as they explore previously unknown areas on a map. (“I wasn’t aware that we had a flag in front of our school.”) They can become more accurate as they study details and layouts (“Oh, the front hall goes all the way from one end of the school to the other.”) And they can be more integrated as they simultaneously touch large areas scaled down to be no more than the span of their two hands (“I hadn’t realized that the three main corridors form a ‘U’.”)

Skills in reading/writing tactile images, or “tactile-graphicity,” develop with lots and lots of carefully sequenced, guided exposure to thoughtfully designed and well-made tactile images. It takes time, strategy, and a steady hand to create tactile maps, but particularly as a dually certified TVI/O&M specialist, I’m completely committed to the process. Why? There’s a danger for concepts of tactile learners to be incomplete, inaccurate, and un-integrated. Tactile maps and other tactile images can be used to address this in the following ways. Learner’s concepts can become more complete as they explore previously unknown areas on a map. (“I wasn’t aware that we had a flag in front of our school.”) They can become more accurate as they study details and layouts (“Oh, the front hall goes all the way from one end of the school to the other.”) And they can be more integrated as they simultaneously touch large areas scaled down to be no more than the span of their two hands (“I hadn’t realized that the three main corridors form a ‘U’.”)

In this post, I describe how I made one of my favorite tactile-maps, along with some of my thinking behind it.

Materials:

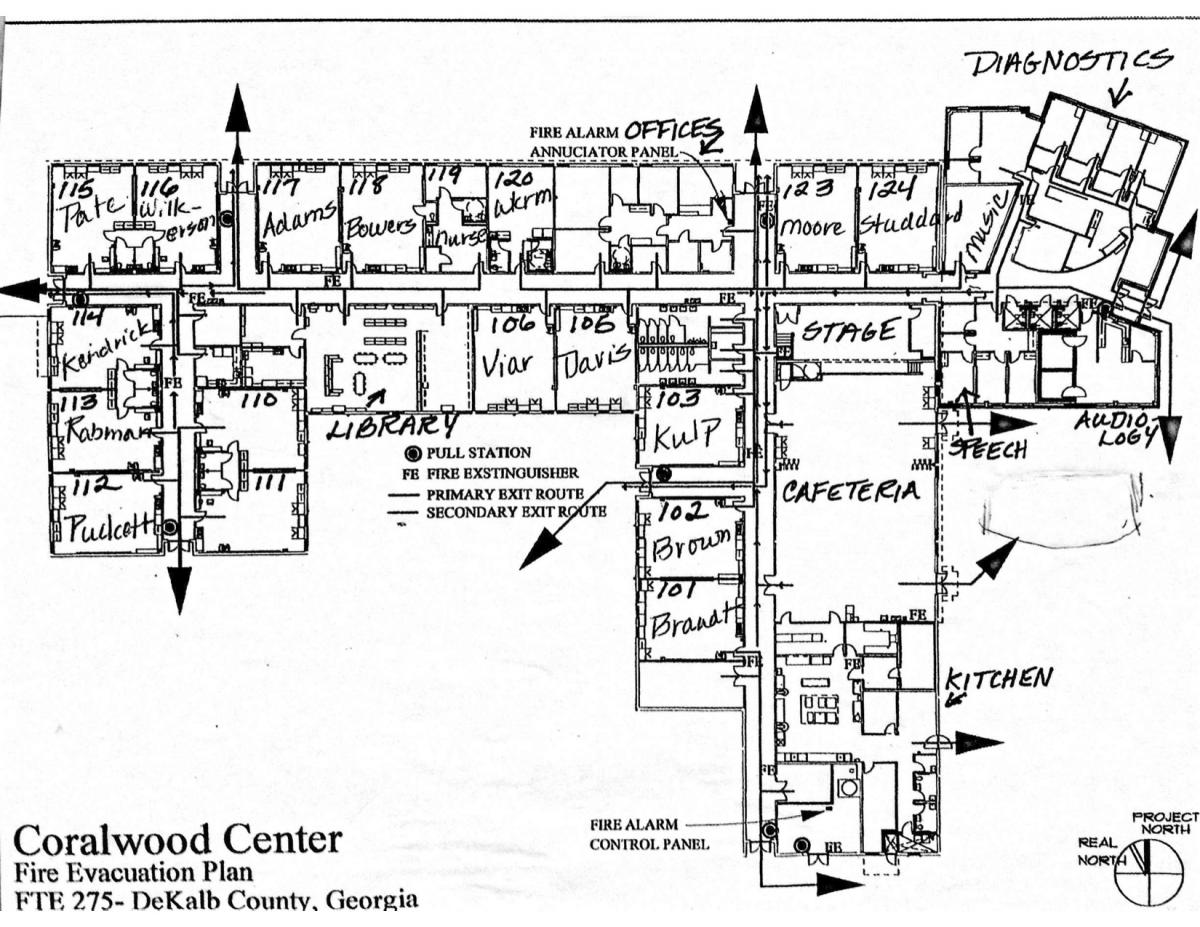

For this map of a school, I began with a print map from the office. Every school usually has them.

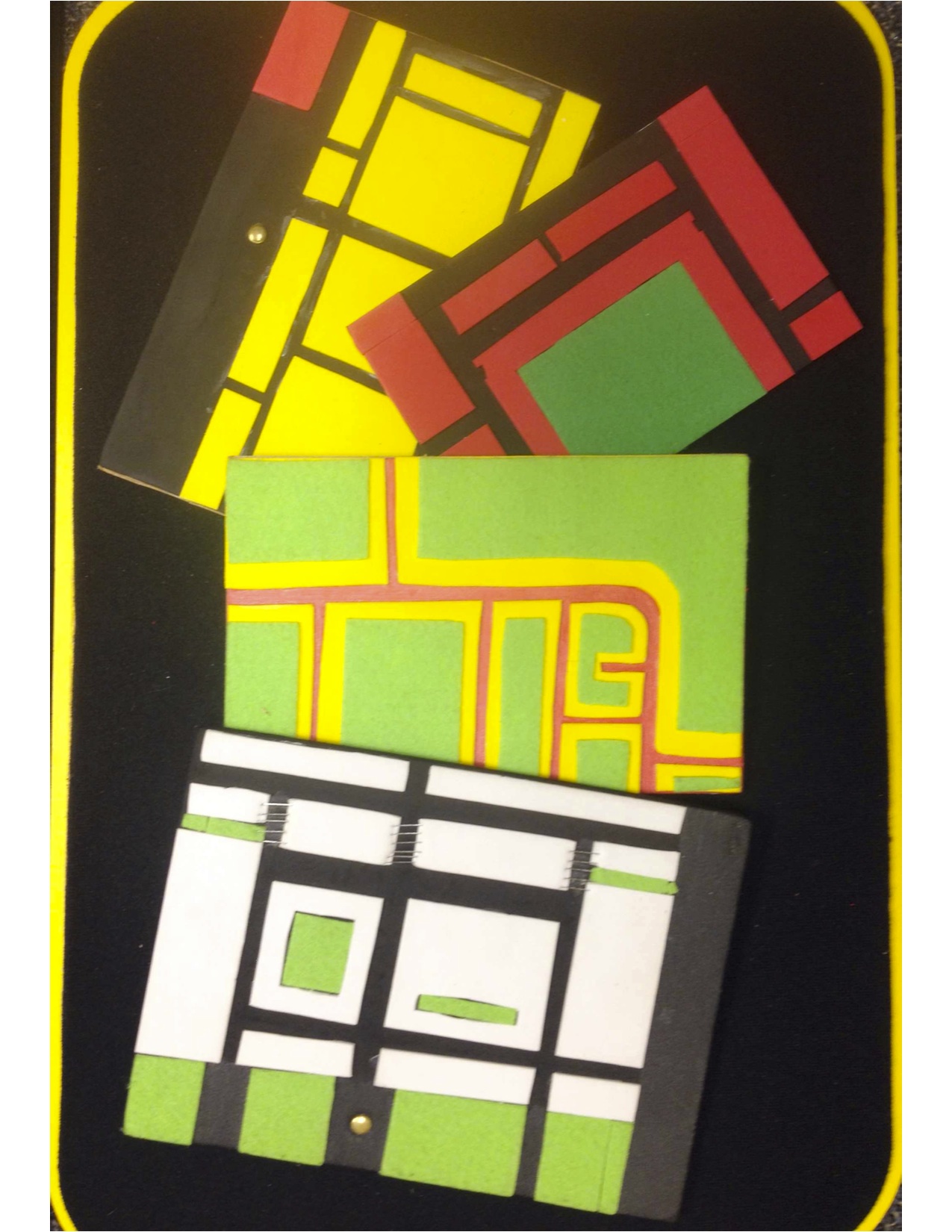

I chose the materials for the tactile map:

- spongy sticky-backed foam for rooms (from a crafts store)

- firm plastic the same size as the print map as the base. Leave the base smooth for hallways and paint with a gritty texture for exterior concrete/hot top surfaces. My plastic base is re-cycled from a book cover. My gritty texture,” Liquitex texture gel” is from an art supply store. Sand can be too abrasive, but paint stores sell softer texture additives I sometimes add to clear glue .

- sticky-backed felt for grass (from a crafts store)

- staples for stairs

- a brass brad/fastener for a flagpole (A flagpole usually indicates the front of a school, and it’s kind of my signature!)

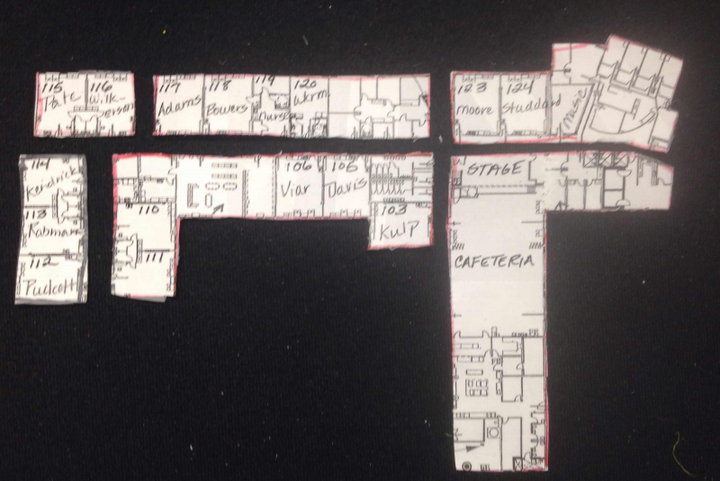

- I taped the print map on top of the sticky-backed foam, then cut through both at the same time to make blocks of rooms, but not hallways.

- I did the same with grassy areas.

- Next, I added the brass brad to the base for the flagpole, and staples to the foam for stairs.

- Then, I dry-fitted all the foam and felt shapes onto the base.

- Once I was satisfied with the fit, I removed the backings and placed the foam and felt permanently.

- My last step was to paint the grit onto the base to represent concrete/hot top areas.

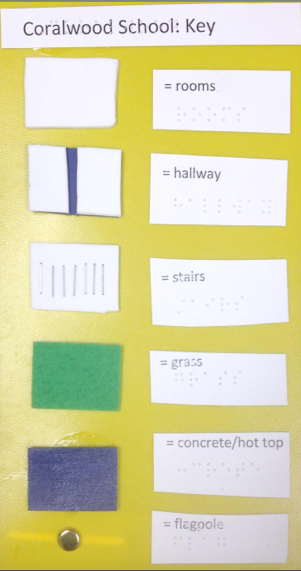

Every map needs a key, so while I was working with each material, I created an extra square to the key. When the map was finished, I mounted these squares and labeled them in braille and print.

There are certainly benefits in placing labels, such as hall numbers and room/street names, directly onto maps. However, my experience has been that when I work with my students with labeled maps, I can’t validly check for their spatial understanding. For example, when I ask them where the 100 hall is, they all too often simply scan the braille/print until they find the label “100 hall,” rather than recognizing it spatially as the North-South hall that is closest to front of the school. If my students are using maps to familiarize themselves with names, I make duplicate maps with labels or I add an overlay of labels to my original map.

There are many materials and techniques for making maps, and extensive guidelines for these including the Braille Authority of North America BANA Website and Lucia Hasty’s Perkins Webinars for both creating tactile-graphics and introducing them to students. The style in this post is my favorite because it’s portable, sturdy, fun for me to make, and my students seem to understand it easily.