By Diane Sheline, TVI, CLVT

Before adapting books and planning literacy materials for students with CVI, please begin by reading:

- Literacy for Children with CVI: Overview and Implications for Different Phases

- Guidelines for Modifying Books for Students in Phases I, II, and III

The books described on this page have been adapted for students with Cortical Visual Impairment or CVI. Each student with CVI has different needs and therefore, books developed for each child should be unique. Teachers, parents and caretakers adapting books for this population will need to take into consideration the student’s interests, information they have obtained through records review, Parent/Caretaker Interviews, informal and formal observations as well as information obtained from formal assessments, including (but not limited to) the Functional Vision Evaluation, Learning Media Assessment, Expanded Core Curriculum and finally, most importantly, the CVI Range.

By having a clear understanding of where the child is visually functioning (CVI Range score) and their unique interests, you are better able to design a book that meets their needs.

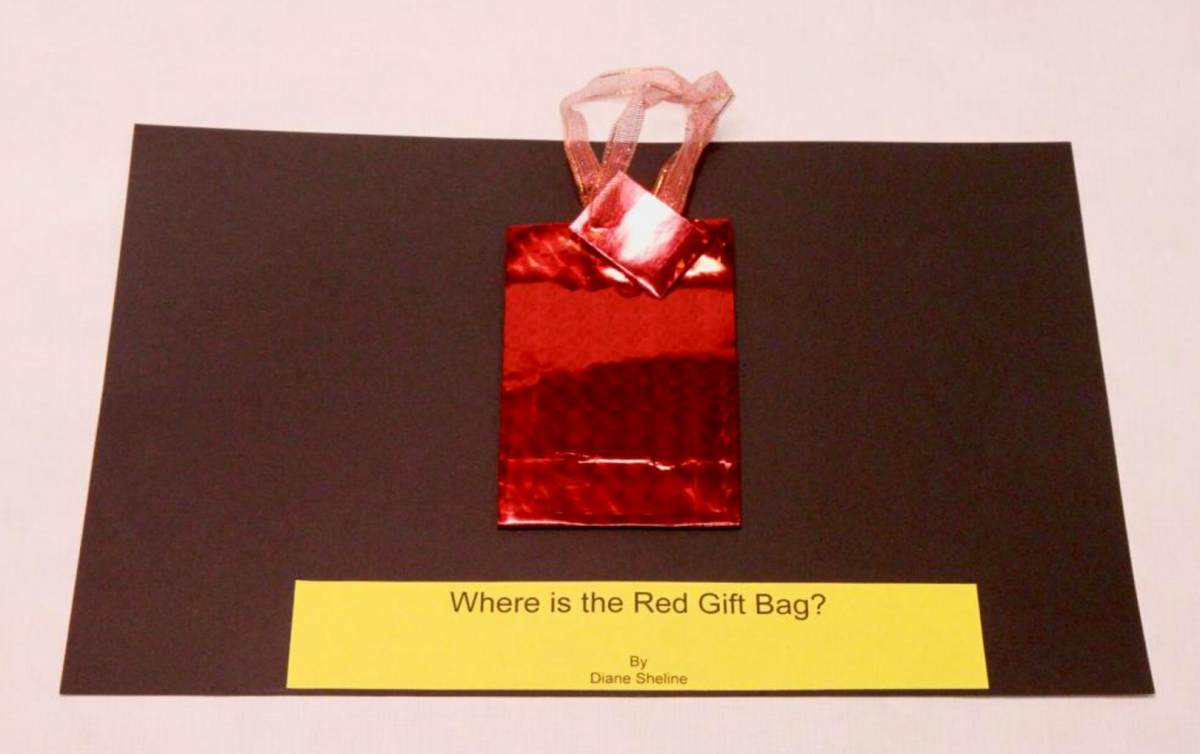

By sharing these books, I hope to spark ideas of subject matter and literacy presentation that might work well for your student. For example, your student or child might be just beginning to use vision and happens to have a special, favorite target. Instead of using the red mylar gift bag I use in the first example, you could swap that out and use your student’s or child’s favorite target (or a representative bit of the favorite target), on the same black paper pages, with “Page Fluffers”, no print, one target to each viewing page or array.

Should the text of the story be included on the page?

Regarding print, I am often asked about whether to put the story lines on the pages or whether the pages should be left blank. Clearly, having the printed story lines on each page causes increased visual complexity in the array for a student who has CVI, and you will need to look closely at the results of the CVI Range to determine whether your student can tolerate that increased complexity. There are, however, several ways to tell a story, including but not limited to, the following;

- Placing the lines of the story on each page as is traditional; careful using this method with students who visually function in Phase I and early Phase II (See “Three Bright Red Pom Poms Lined Up in a Row”)

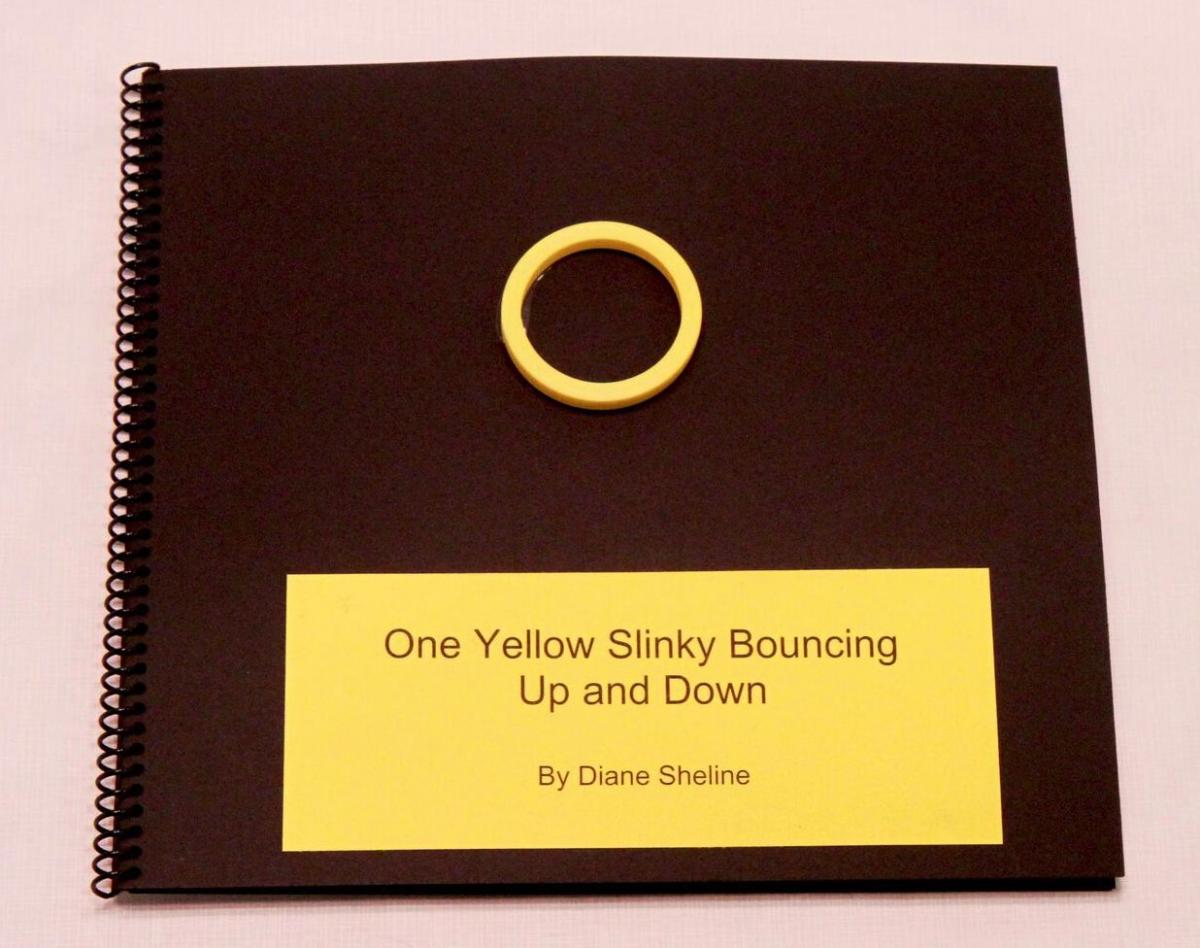

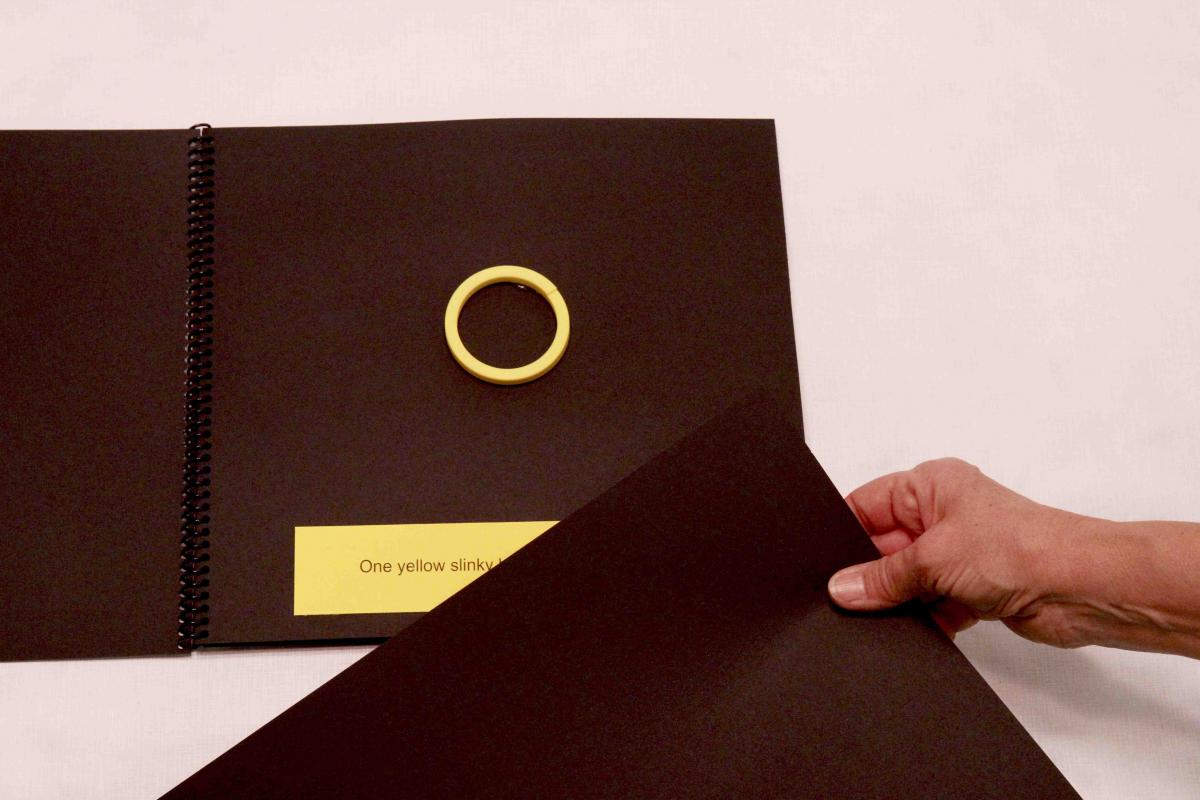

- Placing the lines of the story on each page, but using a Window Card or other Blocking Device to cover the print, until the student can visually attend to both the visual target along with the print. For examples of this strategy, see the sample books, “Clifford’s Family” (the progressive books), as well as “Where is the Red Gift Bag?” and “One Yellow Slinky Bouncing Up and Down”

- Writing the lines of the story on a separate piece of paper and leaving the book pages blank. For an example of this strategy, see the Pegboard Book, “Getting Ready for School”

- Attach sentence strips to black Velcro and they can either be placed on the page or removed.

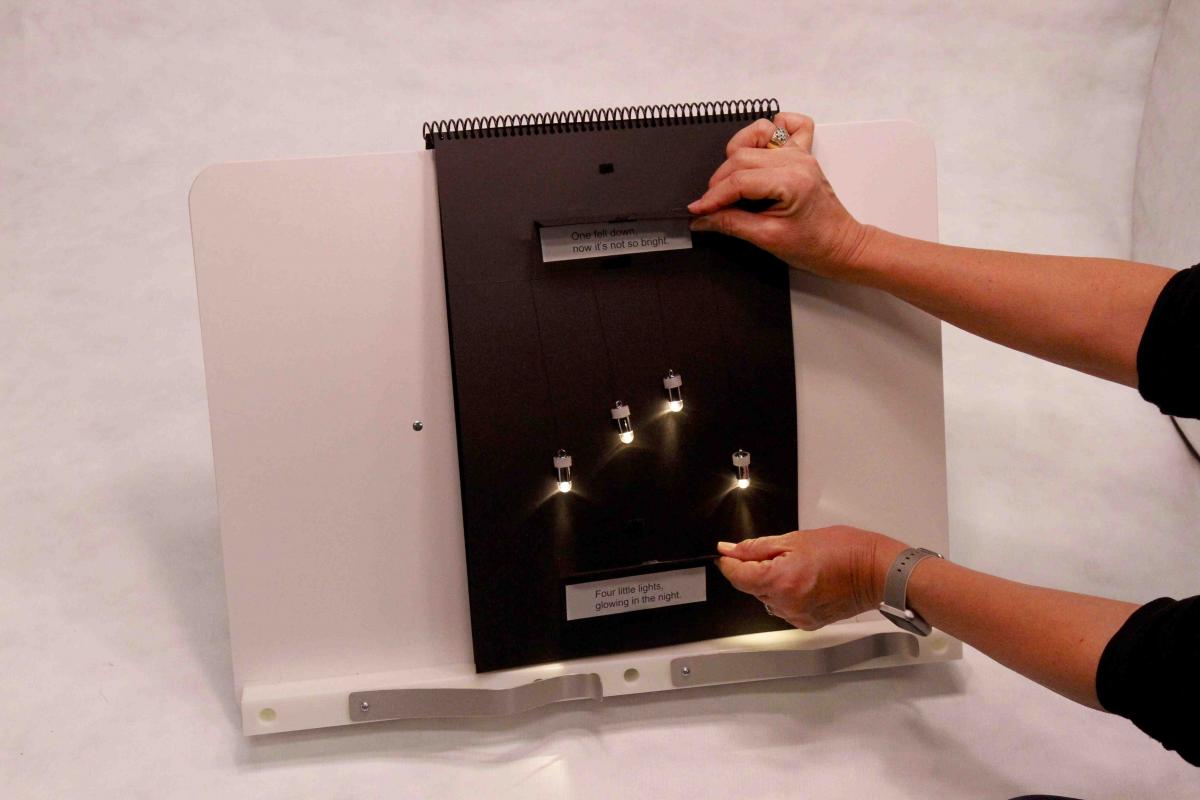

- Have a piece of the page that folds down, to cover the print, using Velcro to hold down the flap or to hold it up. For an example of this strategy, see the sample book, “Five Little Lights”

- Place the target or the picture on the right-side page, and place the sentence(s) on the page on the left, so that you can fold the left page back and behind (removing it from the array), if it causes too much complexity

- Make up the story as you present each page, being careful to note the salient features in the same way each time you “read” the book. For an example of this strategy, see the sample book, “My Favorite Things”.

Beware of Competing Auditory Input

Just as print on a page may cause increased visual complexity that the student may have difficulty with, the same may be said of the competing auditory input that is created as the story is read or sung. This may be particularly difficult for the child who is visually functioning in Phase I and early Phase II. Students who visually function in Phase I often visually attend best if only one familiar visual target is on the page and there is no competing auditory input to distract (i.e. no story is read) or, salient features are only noted after the child looks at the target (see “Where is the Red Gift Bag?” for an example of this strategy). Remember that competing environmental sounds and noises may also be difficult for some students who are just beginning to use their vision.

Create Your Own Book to Meet Needs of Individual Student

Please note that your student may benefit from an idea I have used in one book I share and another idea I demonstrate in a different book. Feel free to “mix and match” and create your own special book to meet the needs of your students. For example, maybe your student loves silver pie tins, but cannot tolerate more than one target in an array. Rather than using 3 silver pie tins, as I use in my sample book, you could use the story idea of the red, mylar gift bag but switch the gift bag out for a single silver pie tin, attaching it (using Velcro) on each page in a different location. You may not want to put in print because the print may cause too much “visual clutter” in the array for your student. Or, you may want to develop a story about a “happy pie tin” with a happy face drawn in black marker on the center of the pie tin, and on the next page he is a “surprised pie tin” or a “sad pie tin”, etc. Use this idea only if your student can tolerate that much complexity on the target itself. For a better understanding of this idea, see the sample books, “Three Silver Pie Tins and One Red Puff” and “Where is the Red Gift Bag?”.

Keep Child’s Developmental Level in Mind

Keep in mind the subject matter of the books you create and the developmental level and/or age of your child or student. The following books discussed were all created for individual students I have worked with who range in age from birth to 5-years and who function developmentally in the same range. Therefore, the subject matter is geared towards young children. Several years ago, I worked with a 12-year-old student who loved Transformers (also called Transformer Robots). I searched and found a book about a Transformer Robot that started off as a red car, but transformed into a red robot (red was this student’s preferred color). I then created a progression of books, like the “Clifford’s Family” books, for this student. Thus, the subject matter was highly motivating for him and more closely matched his developmental level. For a better understanding of this idea, see the sample progressive books for, “Clifford’s Family.”

Create Books Using the Child’s Most Favorite, Familiar Targets

I have found that one of the most important factors to look at when creating or modifying books for students with CVI (in addition to knowing where on the CVI Range they are visually functioning) is understanding what favored, familiar target will be motivating for them. Parents are often helpful in giving suggestions, so make sure to ask. I never would have known that my student (who I note above) loved Transformers had I not asked his mother! In this article, I give many examples of targets that I have used in books, and most are very often used with students with CVI (for example the red pom pom and the yellow slinky). But it will be crucial for you to determine what it is that YOUR child or student likes to look at and then decide whether you can create a book using that target (or a representative bit of that target) or modify an existing book.

Use Hand-Under-Hand Guidance, as Necessary

When tactual guidance is needed to turn a page or explore a target, remember to try to use hand-under-hand guidance and encourage the entire early intervention team to use hand-under-hand guidance as well. As noted at the website for the Georgia Sensory Assistance Project, “Using a hand-under-hand approach, instead of hand-OVER-hand, has been demonstrated to be a far superior way to encourage children to learn with their hands. Instead of moving the child’s hands through actions, the adult’s hands lightly touch beside the child’s or the child’s hands ride on the adult’s hands and feel what the adult hands are doing. In hand-under-hand touching the child and adult explore together, are interested in the object together. The child is invited to feel, not forced or heavily manipulated. Hand-under hand: is non-controlling. lets the child to know how you are touching the same object or what movements your hands make to do a task, and does not keep the child from experiencing the object because he is so aware of your hands controlling his.”

Examples of Books

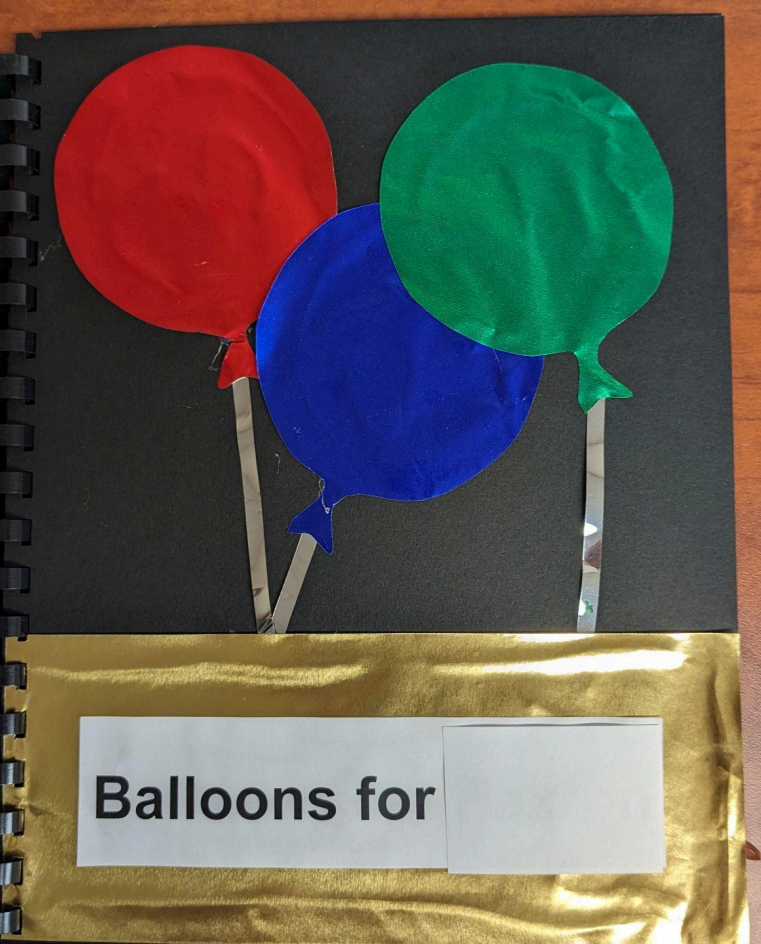

The following are a few examples of books created for students I have worked with:

- Where is the Red Gift Bag?

- Getting Ready for School (CVI-friendly pegboard book)

- One Yellow Slinky Bouncing Up and Down

- Three Silver Pie Tins and One Red Puff

- Three Bright Red Pom Poms Lined Up in a Row

- Five Little Lights

- My Favorite Things

- Clifford’s Family (Modified Version)

For more ideas from Diane Sheline, visit Strategy to See.