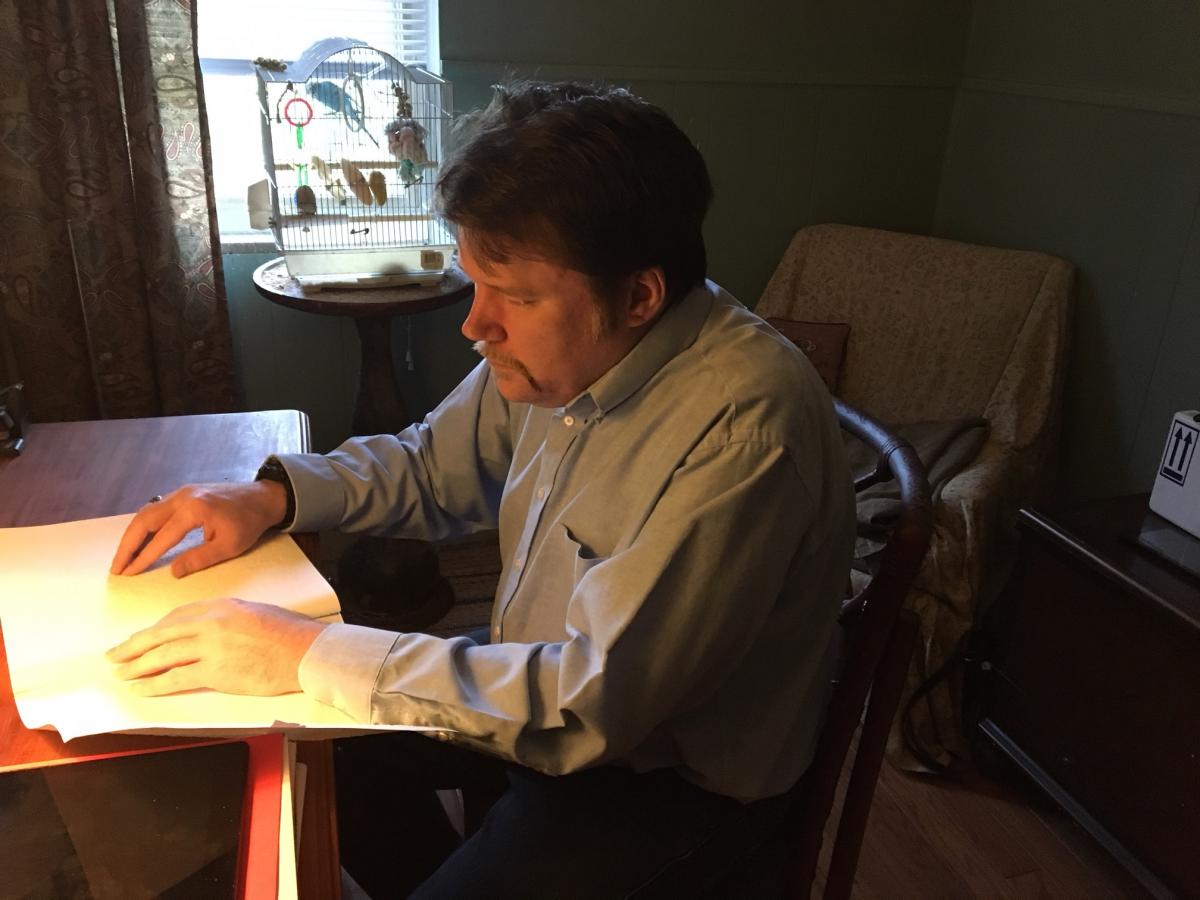

My name is Christopher Sabine, and I am an adult with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia who operates a small consulting firm serving families of children with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia nationally and worldwide. I have worked as a service coordinator at a child welfare agency assisting youth with chronic health conditions and disabilities to transition to adulthood. Most importantly for many families and teachers, however, I am also an adult with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia.

My name is Christopher Sabine, and I am an adult with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia who operates a small consulting firm serving families of children with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia nationally and worldwide. I have worked as a service coordinator at a child welfare agency assisting youth with chronic health conditions and disabilities to transition to adulthood. Most importantly for many families and teachers, however, I am also an adult with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia.

What is Optic Nerve Hypoplasia?

Optic Nerve Hypoplasia (ONH) is an ocular condition that occurs when the optic nerve does not fully develop. This usually occurs in the first trimester of pregnancy for unknown reasons. It can be unilateral (in one eye) or bilateral (in both eyes). Once considered a rare disorder, ONH is fast becoming a leading cause of childhood blindness in the United States.

ONH is associated with several abnormalities of the midline brain, including malformation of many vital brain structures—such as the thalamus and hypothalamus. These brain structures control many crucial bodily functions, such as sleep wake cycles, body temperature regulation, sensory processing and behaviors. The ability of a child with ONH to produce vital hormones may also be affected.

ONH is a spectrum disorder; a child with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia can be totally blind, but exhibit no developmental delays, sensory processing difficulties or medical complications. Another child can have relatively good visual acuity but have significant medical complications such as pituitary deficiencies or significant behavioral, emotional or intellectual disabilities.

The vision of a person with ONH can range from near normal usable vision to total blindness. Nearly all children with ONH exhibit random, horizontal and vertical eye movements called nystagmus. Some children may also exhibit strabismus, which is a crossing or turning inward of the eye. This is sometimes colloquially referred to as “lazy eye”. It is important to understand that for the child with ONH, strabismus and nystagmus are involuntary; he/she is entirely unaware of these eye movements. However, nystagmus and strabismus can make focusing on objects or attending to visual tasks, such as reading print for any length of time, difficult to impossible.

What Other Challenges Accompany ONH?

Many children with ONH have difficulty processing sensory information through some or all of their senses—referred to as sensory processing disorder. They may show sensory defensiveness and delays in learning fine and gross motor skills, which can make reading braille and learning basic daily living skills, like dressing, grooming and personal hygiene, difficult or impossible without additional supports. Delays in speech, language, and communication are fairly typical. Many children with ONH also exhibit self-stimulatory behaviors—such as repetitive rocking and hand-flapping—that are difficult or impossible to manage without additional interventions. These behaviors are sometimes referred to as repetitive, stereotyped behaviors or “blindisms”. Many, like me, exhibit behaviors and developmental delays typical of children on the Autism Spectrum.

Some children with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia lack a triangular structure near the brain’s midline called the Septum Pellucidum and qualify for the additional diagnosis of Septo Optic Dysplasia (SOD). However, recent research indicates that children with Septo Optic Dysplasia show the same medical, developmental and psychosocial characteristics as other children with ONH and an intact Septum Pellucidum.

Identification of ONH: A Personal Experience

In my case, my parents noticed that something was different about me when I was six months old when I began looking directly into the sun. They also noticed that my eyes were moving randomly inside their sockets. My mother took me to an ophthalmologist, who diagnosed me with Bilateral ONH.

Though I could walk while holding on to objects at nine months, I did not walk unsupported until twenty months. According to my mother, while I could understand what my parents said to me at ten months, I did not speak until I was three years old. When I did begin speaking however, it was in complete sentences. I did not go through a babbling stage like most typically developing children. As I’ll mention later, this pattern of learning new skills is not uncommon in children with ONH.

My Educational Development

I quickly learned to count and play music. I taught myself how to play the piano, but I lost interest and the ability to play when I started attending mainstream school. I loved to listen to the sounds of cars, especially the sounds their horns made when they honked or their ignitions started. My favorite word was “beep.”

I eventually learned every area code in North America and could recite full articles from “National Geographic World” magazine when I was in first grade. I later learned to recite the first 103 elements of the Periodic Table and taught myself to perform long multiplication problems inside my head.

Learning braille and many daily living skills were another story entirely, however. I attended a preschool for blind children, where I began my first unsuccessful attempt to learn braille. I found that memorizing how the dots on the page were supposed to form words was a frustrating and exhausting effort for me. I remembered once being so frustrated recognizing the letter “e” in the word “horse” in the children’s braille learning series I was reading that I had a crying meltdown. Braille’s abrasive texture made processing it especially difficult. Since I have a small amount of usable vision, my parents and teachers decided to abandon braille in favor of recorded books and print reading with a closed circuit television.

Behavior Challenges and ONH

I had some challenging behaviors all through childhood—including rocking, hand flapping, picking my lips and crying meltdowns when frustrated, overstimulated, distressed or anxious. Like many children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, I had very strong, pervasive areas of interest that functioned as obsessions. These included the sounds of local and long distance telephone equipment, certain musical groups and artists, the Periodic Table of the Elements and the geography of specific areas of the United States—particularly my local area and, later, Northern and Central New Jersey. I also developed strong attachments to certain teachers. These areas of interest were very pervasive and difficult, if not impossible, for me to redirect. Some persist in some form to this day. It took extra time for me to process information, which made reading comprehension particularly challenging.

I was unable to dress myself until I was in sixth grade and could not button or tie my shoes until almost the beginning of my freshman year of high school. I attended mainstream classes all through grade school and high school. I had eight years of pull out occupational therapy, speech therapy and orientation and mobility instruction through my local school district. After the summer of my sixth grade year, my mother enrolled me in a summer program for children with blindness and visual impairments in the city where I live. I attended that program for three summers and was finally able to learn many daily living skills, including cane travel. I also—significantly—learned to button my shirt and tie my shoes at the end of my third year of this program.

High School Brings Success with Braille and Other New Skills

Just after I learned to tie my shoes—at the start of my freshman year of High School—something interesting happened. Learning new skills and processing information spatially became much easier for me than it had been in the past. Like learning to speak when I was three, I found that I could button my shirt, tie my shoes and perform some other skills like plugging in appliances with some ease—as if I had been using these skills all my life.

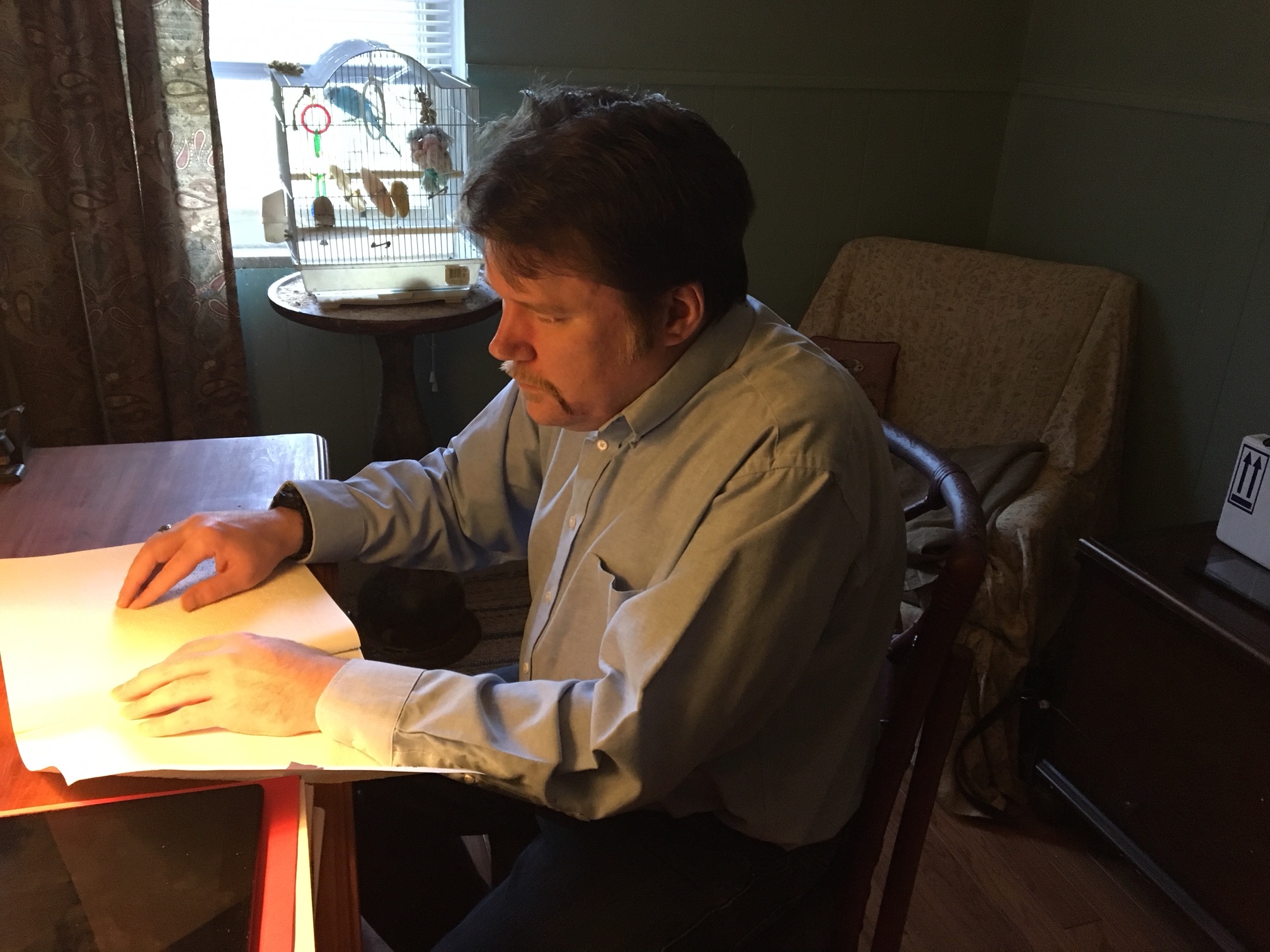

The next summer, I made another attempt to learn braille—with the support of a vision consultant and a transitions specialist at my state’s office of vocational rehabilitation. I found that I could read the first ten letters of the braille alphabet and—by extension—the numbers 1 through 0 with ease. When I started this second attempt to read braille, memories of my initial attempt in preschool came flooding back, as if my brain finally had installed the hardware and software drivers necessary to decode braille letters and determine how to perform other fine motor skills—software it did not have in preschool. I believe this came about because of the constant efforts and repetition involved in learning these skills.

While I did not master braille at that time because of the demands of high school and college, I did eventually learn to fully master braille as an adult and am a fairly fluent braille reader—though my speed is not up to my liking.

In my practice, I have heard families describe similar patterns of learning some skills—particularly speech. One child who was considered functionally nonverbal and unable to read reportedly sat his mother by the family’s television and began reading the text from a Sesame Street broadcast out loud. While attending a self-contained classroom with primarily nonverbal students with significant intellectual disabilities, he had taught himself the alphabet and basic phonetics by watching Sesame Street.

During my first two years of high school, I developed strategies to minimize many of my behaviors and was able to stop rocking and hand-flapping entirely. These strategies are highly individualized, and I could devote an entirely separate blog post describing them.

My Life as an Adult with ONH

I eventually graduated from high school with honors, received my Bachelors and a Master’s degree in Social Work and worked full time in professional human services for five years. However, I left full-time social work after job-related stress caused some inappropriate behaviors to reemerge.

In 2005, I launched ONH Consulting to support children with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia and related conditions and their families, drawing on my professional social service background and personal experience as someone living with ONH. My business, ONH Consulting, provides service coordination, personalized guidance, IEP consultation and community referrals to families of children with Optic Nerve Hypoplasia, Septo Optic Dysplasia and related diagnoses.

As local school districts nationally are faced with increasing numbers of blind and visually impaired children with ONH nationally, I believe a model of best practice needs to take shape to meet our children’s specialized and unique learning needs. I hope that my experiences— and those of other adults with ONH—will help bring this about.